The recent killings of Black Americans have reignited calls for policing reform, including proposals to diversify police departments, which have historically been made up of primarily white, male officers. Yet, few studies have examined whether deploying minority and female officers actually changes police-civilian interactions or reduces instances of shootings and reported misconduct.

A study first debuted Feb. 7 at the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) 2021 Annual Meeting harnesses newly collected data from the Chicago Police Department to show that deploying officers of different backgrounds does, in fact, produce large differences in how police treat civilians.

The researchers link millions of daily patrol assignments with police officer demographics to show that Black and Hispanic officers make far fewer stops and arrests and use less force than white officers, especially against Black civilians, when facing otherwise common circumstances. Hispanic officers also engage in less enforcement activity. Female officers of all races also use less force than males.

The findings, featured on the cover of the Feb. 12 issue of the journal Science, suggest that increasing diversity within police departments may decrease police mistreatment of minority communities.

“A first step in assessing the impact of diversity policies is to test whether officers with different demographic profiles actually do their jobs differently while holding circumstances constant,” said study co-author Jonathan Mummolo, assistant professor of politics and public affairs at the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs. “Using rare microlevel data on when and where thousands of officers are deployed over time, we are able to make these comparisons, and we find substantial disparities in officer behavior even when facing comparable places, times and civilians.”

Mummolo co-authored the paper with Bocar Ba of the University of California, Irvine; Dean Knox of the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania; and Roman Rivera of Columbia University. Mummolo and Knox have published a number of studies together in recent years looking at policing tactics and reforms in the United States.

Given the recent widespread calls for law enforcement reforms, especially following the death of George Floyd in 2020, the researchers wanted to determine how the deployment of officers from different racial, ethnic and gender identities might affect the treatment of civilians.

They used new, high-resolution data on police personnel activity in Chicago, which has a history of racial tensions between residents and the police. This microlevel data indicated not just that an arrest had happened, but where, by whom, at what time, on what charge, plus many features of the civilian and officer involved. Chicago provided an invaluable opportunity to study diversity in policing as both the city and department are highly diverse.

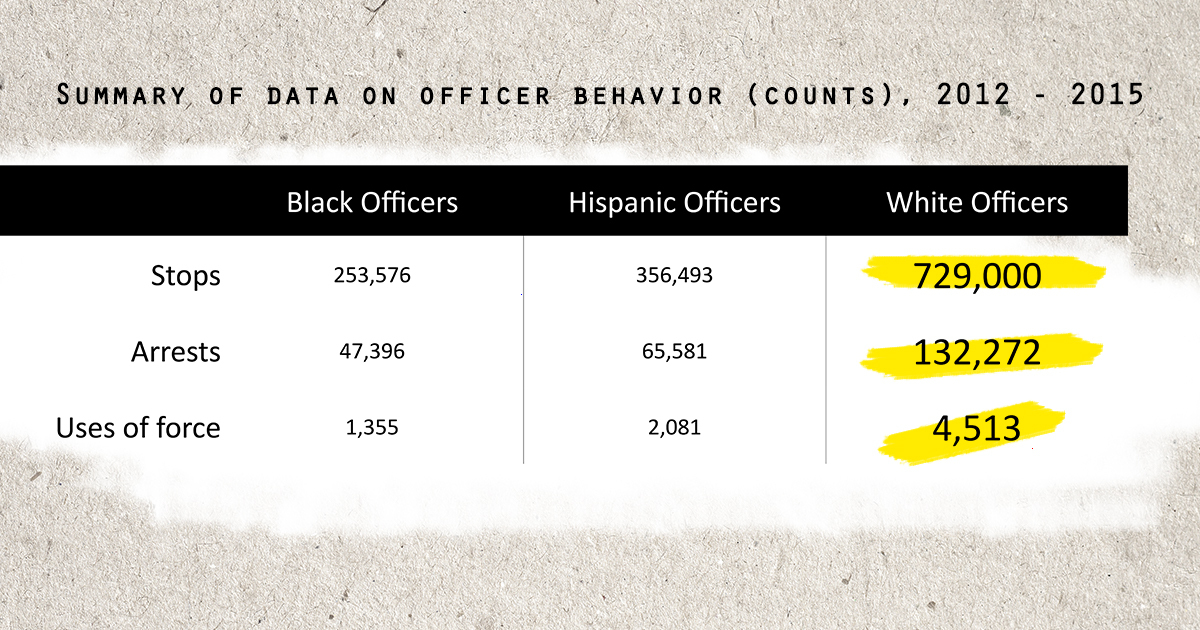

The researchers drew on data assembled through years of open records requests, which included the race and ethnicity, language skills, daily shift assignments and career progression of roughly 7,000 individual officers. They then linked these files to time-stamped, geolocated records of those officers’ arrests, traffic stops and use of force against civilians from 2012-15. These data included 2.9 million officer shifts and 1.6 million enforcement “events.” Due to limited data, the researchers only looked at only Black, Hispanic, and white officers, which made up 97% of the of the sample.

The researchers then created a dataset documenting the circumstances and outcomes of each officer-shift, to allow for comparisons of officers of different demographic profiles working in highly similar places and times. This allowed them to see how officers of different backgrounds behaved in similar circumstances.

They found Black officers made substantially fewer stops, arrests and uses of force per shift than white officers, reductions equal to 29%, 21%, and 32% of average white officer behavior citywide. The findings are similar for Hispanic and female officers, though the differences are more modest.

“These patterns are remarkably in line with the hopes of proponents of racial diversification, which seeks to reduce abusive policing and mass incarceration, especially in Black communities,” Mummolo said.

While the researchers cannot discern bias or intent based on these data, one explanation for the differences could be racial bias, they said. Further study with additional data is needed to understand the mechanisms behind these differences in police behavior.

The study also stresses that the effects of diversity in policing are more complex than often recognized. While this study focused on race, ethnicity and gender, police officers are multidimensional human beings. This means enacting effective personnel reforms will likely require thinking beyond these categories. Nevertheless, the study provides a framework for other scholars to evaluate and re-evaluate the effects of diversity in policing in America.

On Monday, Feb 8. at 9 a.m. EST, AAAS and Science held an embargoed briefing on the study, “The role of officer race and gender in police-civilian interactions in Chicago,” which was published by Bocar A. Ba, Dean Knox, Jonathan Mummolo, and Roman Rivera Feb. 12 in the journal Science.