Fatima went into labor with her first child at the age of 16. As is custom in her nomadic community in western Sudan, she planned to deliver the baby at home. But after three days of complications, she embarked on a half-day trek by camel to the nearest hospital. When she arrived, her baby was delivered stillborn by Caesarian section. But Fatima’s journey did not end there.

Fatima went into labor with her first child at the age of 16. As is custom in her nomadic community in western Sudan, she planned to deliver the baby at home. But after three days of complications, she embarked on a half-day trek by camel to the nearest hospital. When she arrived, her baby was delivered stillborn by Caesarian section. But Fatima’s journey did not end there.

Fatima’s prolonged labor caused an obstetric fistula – a hole between the vagina and rectum or bladder. The only solution is surgery, which she couldn’t afford. After returning home, her husband divorced her, blaming the smell created by the continuous leak of urine caused by the injury.

The Fistula Foundation funds more obstetric fistula surgeries than any other non-governmental organization in the world. When Kate Grant MPA ’94 joined the Foundation as its first CEO in 2005, it supported surgeries at one institution in Ethiopia. Since then, the Foundation has helped women in 29 countries in Africa and Asia.

Fatima received surgery at a treatment center funded by the Foundation. The accompanying psychological rehabilitation eased the depression that had overtaken her life, allowing her to reclaim her dignity. She now advocates for maternal health and runs her own small business in her community. Fatima is planning for her future, including remarrying and having children.

Data can be difficult to collect due to the condition’s associated isolation and shame. However, a recent

meta-analysis published by the London School of Tropical Hygiene & Medicine looked at all relevant studies in the region’s low- and middle-income countries. The report estimates one million women are suffering from obstetric fistulas.

The injury is preventable and treatable. In wealthier countries, the once-prevalent condition is almost unheard of, thanks to healthcare access. If a labor is prolonged, a woman typically has a C-section before complications ensue. In the world's poorest countries, an obstructed labor might last six or seven days, with the baby’s head forced against the mother’s pelvic bone with each contraction. The restriction of blood flow kills the tissue, creating the abscess. The baby dies in 90 percent of cases. If the mother survives, surgery and care cost several hundred dollars – more than the annual salary for most people in the region.

The injury is preventable and treatable. In wealthier countries, the once-prevalent condition is almost unheard of, thanks to healthcare access. If a labor is prolonged, a woman typically has a C-section before complications ensue. In the world's poorest countries, an obstructed labor might last six or seven days, with the baby’s head forced against the mother’s pelvic bone with each contraction. The restriction of blood flow kills the tissue, creating the abscess. The baby dies in 90 percent of cases. If the mother survives, surgery and care cost several hundred dollars – more than the annual salary for most people in the region.

Instead, a woman will cope with the fistula, sometimes for decades. She is often abandoned to live alone, meaning the burden is not only physical, but psychological. The New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof, an author and advocate for women’s rights, says the untreated women are looked on as “the lepers of the 21st century.”

Kristina Graff MPA ’05, director of Global Health Programs at the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs’s Center for Health and Wellbeing, said the rate of occurrence reflects the state of women’s and maternal health.

“It is a mark of failure in terms of meeting a population’s needs,” Graff said. “Women are not the primary decision-makers regarding pregnancy and childbirth. Once the fistula occurs, they are hidden even more.”

But Graff noted that the women should not be viewed as victims.

“Those who make it to surgery have often walked miles and overcome tremendous hurdles to receive treatment,” Graff said. “They have been structurally disempowered, but through their own strength, they survive.”

“Those who make it to surgery have often walked miles and overcome tremendous hurdles to receive treatment,” Graff said. “They have been structurally disempowered, but through their own strength, they survive.”

It was on a seven-month trip through this region that Grant realized she needed to leave her advertising career for a new path.

“Going into the developing world, it’s hard not to see that women are not as empowered as they could be,” Grant said. “It was a literal journey that started opening my mind to the world’s problems.”

Volunteering at Planned Parenthood showed Grant an avenue for action, but she wanted to broaden her scope. After completing the Wilson School’s MPA program, Grant served as professional staff member for the House Foreign Affairs Committee and deputy chief of staff at the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). She has been a consultant to USAID’s Mission in Tanzania, the Rockefeller Foundation, the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative and the Women’s Funding Network.

Grant sees her experiences as cumulative training for her current role: she gained a theoretical understanding of policy from the Wilson School, practical skills from working in public affairs and a talent for translating the Foundation’s message from her advertising days.

When her career led her back to Africa, she visited an obstetric fistula hospital by chance.

“My heart was captured,” Grant said. “I’m very taken by this cause. I’m able to throw my life force, for what it’s worth, against it. These women are often so young and grievously injured. They’re very courageous, but they live in countries where their needs are not necessarily looked after. For us to be able to support life-transforming surgery is unambiguously good."

Grant credits the Foundation’s success to its tenacious focus.

“We care about the women giving birth without emergency obstetric care, but we’re focused on getting treatment for the one million women who haven’t gotten the attention their injury warrants,” Grant said. “Oftentimes, the countries in which we work are struggling with a number of issues related to extreme poverty, sometimes political turmoil, military instability – complicated problems, and fistula is just one of many they’re confronting.”

The world is filled with profound problems, and it can paralyze you if you can’t make peace with, in your one and only life, being able to make progress on one of them. So deliberately, we said we’re going to choose an appropriately narrow focus, and then we’re really going to swing for the fences.”

Last year, the Fistula Foundation treated nearly 4,500 women. Now that they have spread to 29 nations, they plan to go deeper into select countries to reach women in the very remote areas – the most likely to be suffering in silence.

Grant acknowledges the story is a challenging one to tell. The Foundation overcomes this by communicating the essence of what’s most important.

“What we talk about is how people can help women who have been grievously injured simply for trying to bring a child into the world to not suffer further,” Grant said. “At the end of the day, that’s really what we’re about.”

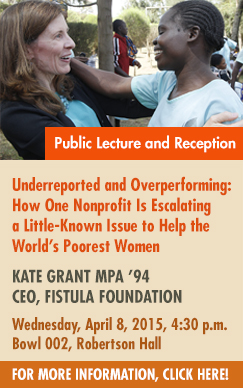

Kate Grant will give a public lecture at the Wilson School Wednesday, April 8, 2015. For more information, click here.