Ebola is difficult to contract. The disease is not airborne like influenza or Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) – a healthy person must come in direct contact with the fluids of an infected, symptomatic person to risk transmission. The count of deadly cases of Ebola is continuously exceeded by the mortality rates of malaria, tuberculosis and other illnesses in West Africa. This is why the alarms sounded so loudly when the number of Ebola fatalities spiked in the summer of 2014.

The degree of the outbreak was not necessarily reflective of the biological complexity of the disease itself, but rather the dire state of the global health system. Still recovering from a civil war, Sierra Leone’s government is weak, and distrust pervades the culture. People live in extreme poverty in the country and neighboring Guinea and Liberia, surviving on pennies a day. The simple gloves and protective suits that could halt the infection of caretakers, who are the most likely to contract the disease, were unattainable, much less the oversight needed to manage the epidemic.

The sudden strain placed on the region’s national health care systems choked the already-weak regional economy, threatening the global economy and provoking an international call to action as whole countries began to seemingly dissolve. The worldwide galvanization sent funds, resources, healthcare workers and even military aid, which drastically helped to slow the spread of Ebola. But the threat of infection is still palpable in the region and in the media; medical professionals are working tirelessly, and many continue to suffer the physical and emotional ravages of the disease. Still, it is not only the human element keeping policymakers and aid workers awake at night. It’s the question of how to prevent such a catastrophic outbreak from happening again.

“When an epidemic strikes, the public response tends to fall into a few pre-determined categories: the tragedy that has befallen the afflicted, heroic efforts to help and the possibility that science and medicine will find a cure,” said Janet Currie Ph.D. ’88, the Henry Putnam Professor of Economics and Public Affairs at the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, chair of Princeton's Department of Economics and director of Princeton University’s Center for Health and Wellbeing.

“If we are to prevent such disasters in the future, we need a richer understanding of other aspects of the story: the political and economic barriers to an effective response, the way that history shapes the conditions that give rise to the epidemic and the societal factors that either limit or magnify the epidemic."

“If we are to prevent such disasters in the future, we need a richer understanding of other aspects of the story: the political and economic barriers to an effective response, the way that history shapes the conditions that give rise to the epidemic and the societal factors that either limit or magnify the epidemic."

To expand on this perspective, the Princeton-Fung Global Forum will convene Nov. 2–3 in Dublin, Ireland, to examine global health, using the Ebola outbreak as a case study of a modern plague. The third annual forum will include academic scholars, researchers, health and medical professionals, aid workers, policymakers and journalists. Using a multidisciplinary approach, panelists will examine economic, environmental, political and historical issues in addition to those of health and medicine to draw lessons from the current outbreak and devise methods to prevent modern plagues going forward.

Several panelists are Princeton and Wilson School alumni who have been directly involved with global health efforts and battling the recent Ebola outbreak. Many of them are on the ground in West Africa.

Douglas Mercado, who received his master’s degree in public policy in 2007, is the team leader for the United States Agency for International Development’s (USAID) Disaster Assistance Response Team (DART), which is spearheading the U.S. response to the crisis. Stationed in Liberia, Mercado oversees the West African region. While resolving the crisis at hand, DART has also clinically trained approximately 1,500 Liberians in an effort to make an enduring improvement to the country’s healthcare system. The group hopes to put into place mechanisms so that the country can better manage future crises.

In addition to training and equipment, a pivotal factor in the success of these relief and prevention efforts is an understanding of each country’s culture and people. To this end, Raphael Frankfurter ’13 has focused his efforts on building trust between the community and medical professionals in Sierra Leone. He spent summers during his undergraduate Princeton years working with an organization that provides healthcare in Sierra Leone, the Wellbody Alliance, to repair the post-war healthcare system in that country. In his current position of executive director of the organization, he has developed an understanding of the intricacies of outreach efforts, a necessity for designing realistic approaches to rebuilding the country.

Alongside cultural sensitivity is data-driven epidemiology – the root of discerning the science of disease transmission and prevention. And that’s where Rebecca Levine ’01 comes in. Shortly after earning her Ph.D. in the ecology and epidemiology of infectious diseases from Emory University in 2014, Levine joined the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as an officer in the Epidemic Intelligence Service – known as the “disease detectives” – and the U.S. Public Health Service, in the Division of High-Consequence Pathogens and Pathology. She was immediately deployed to West Africa and has served three rounds in Sierra Leone providing epidemiological assistance to the Ministry of Health, which includes case-finding, contact-tracing, data management, and training of local staff – all essential measures to determining the course for intervention.

Alongside cultural sensitivity is data-driven epidemiology – the root of discerning the science of disease transmission and prevention. And that’s where Rebecca Levine ’01 comes in. Shortly after earning her Ph.D. in the ecology and epidemiology of infectious diseases from Emory University in 2014, Levine joined the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as an officer in the Epidemic Intelligence Service – known as the “disease detectives” – and the U.S. Public Health Service, in the Division of High-Consequence Pathogens and Pathology. She was immediately deployed to West Africa and has served three rounds in Sierra Leone providing epidemiological assistance to the Ministry of Health, which includes case-finding, contact-tracing, data management, and training of local staff – all essential measures to determining the course for intervention.

A research associate with Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF, or Doctors without Borders in the United States), Princeton undergraduate and graduate alumna Kimberly Bonner ’08 MPA ’12 witnessed the results of relief efforts at the Ebola Treatment Center in Freetown, Sierra Leone. While not a spokesperson for the organization, Bonner worked as a communications officer for MSF at the Center from December 2014 to February 2015.

“As the outbreak recedes, we can't afford to miss the opportunity to strengthen the health systems of these Ebola-affected countries,” Bonner said. “While Ebola has directly affected thousands of families, the secondary effects on the health system and the economy have been even larger. In Sierra Leone, mortality is projected to increase by 20 percent for pregnant women and children under five. Hamstrung vaccination efforts over 18 months could lead to nearly a doubling of cases in a measles outbreak, with thousands of additional children dying.”

As determined by a recent study co-authored by panelist Bryan Grenfell, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology and public affairs at the Wilson School, closings and fear of healthcare centers during the outbreak limited preventive care. Lessons learned from the Ebola epidemic will need to be reflected in a swift mobilization effort to carry out a comprehensive vaccine campaign against measles, and minimize the risk of everlasting damage to West Africa’s public health.

As determined by a recent study co-authored by panelist Bryan Grenfell, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology and public affairs at the Wilson School, closings and fear of healthcare centers during the outbreak limited preventive care. Lessons learned from the Ebola epidemic will need to be reflected in a swift mobilization effort to carry out a comprehensive vaccine campaign against measles, and minimize the risk of everlasting damage to West Africa’s public health.

However, while this virus has demonstrated Africa’s health vulnerabilities, an evaluation of the handling of the crisis both regionally and globally is beginning to take shape. The Princeton-Fung Global Forum will bring together the varying viewpoints to help frame the conversation and explore proposals for managing future crises.

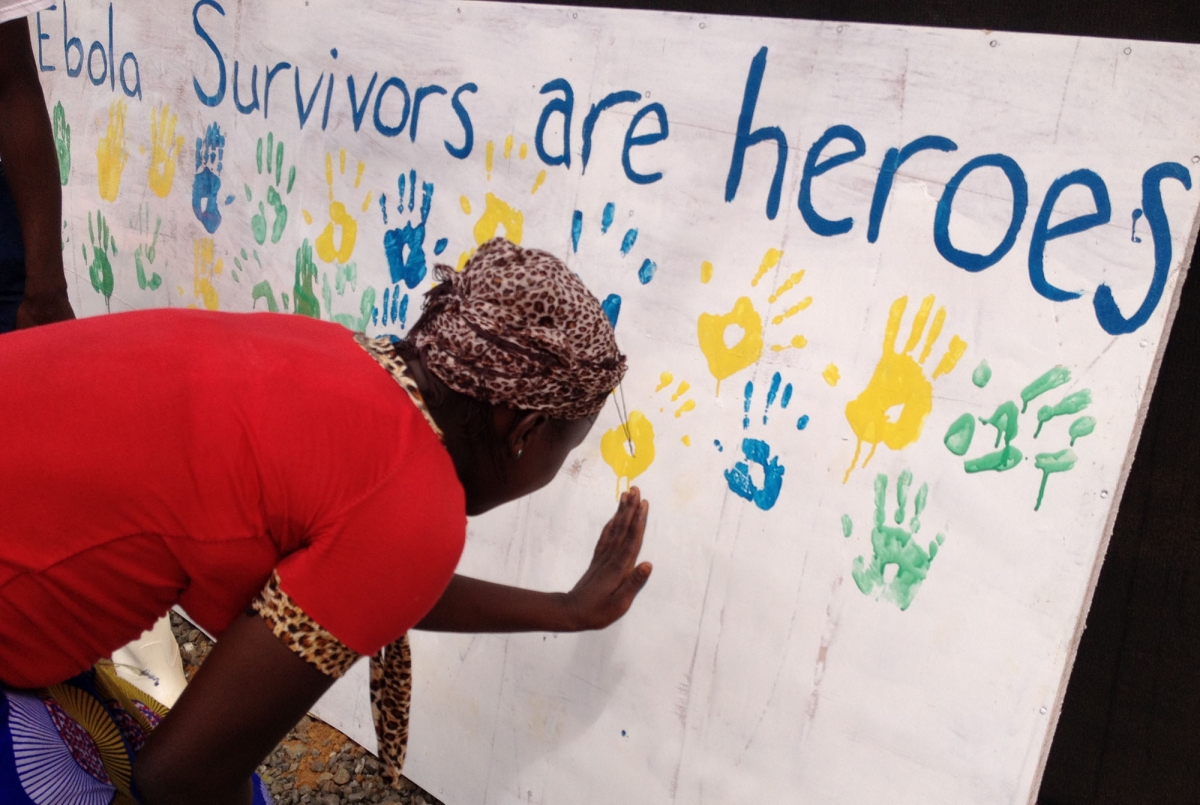

The media coverage of the Ebola crisis has helped many in the international community connect to a cause that was, at first, easy to ignore. With resources and foreign workers streaming in, human resilience in these communities has demonstrated that if others fight, so will they. The question is morphing from if sound investment can be made to how it can be made.

Above all, it is not only empathy and humanitarianism driving the effort for understanding – it is the reminder that no one lives in isolation. That the suffering of a tiny fraction of the West African population can decimate countries and make waves this size is evidence that international aid and oversight policies affect every single person globally, regardless if they would never have been at risk for transmission, and even if they had never heard of “Ebola.” Fortunately, the perseverance seen in the disease-ridden and their caretakers permeates people across professions and disciplines. Their work is not yet done.