Half of the 220,000 people killed in the Syrian civil war have been civilians. Untargeted barrel bombings have crumbled cities and diminished basic resources like food and water. Many children have been out of school for four years. Those who have survived the attacks suffer with injuries and have no access to medical care.

Within the country, 7.6 million people have been displaced. Another 4 million have made the life-threatening trek into neighboring countries – Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq and Egypt – making this the worst refugee crisis since the Rwandan genocide two decades ago.

Watching the Syrian tragedy unfold in real time, Jeremy Barnicle, MPA ’04, chief development and chief communications officer at the global aid agency Mercy Corps, doesn’t see an end to the crisis in the near future.

Watching the Syrian tragedy unfold in real time, Jeremy Barnicle, MPA ’04, chief development and chief communications officer at the global aid agency Mercy Corps, doesn’t see an end to the crisis in the near future.

“In my roughly 20 years working in and around conflicts, Syria is the most worrying because people are suffering massively,” Barnicle said. “It has destabilized the region well beyond its borders, and it’s hard to see it ending soon.”

The Syrian crisis sprung from the series of protests that erupted across the Middle East and Africa in 2011, known as the Arab Spring. Largely incited by dissatisfaction with government and living conditions, more than 20 countries faced unrest from public demonstrations to overthrown regimes to all-out civil war. In Syria, dissent quickly escalated to an armed rebellion. With stability further complicated by the rising influence of the militant group known as the Islamic State, the war shows no signs of winding down. Tension among Syria’s neighbors continues to grow as they bear the weight of the civilian exodus.

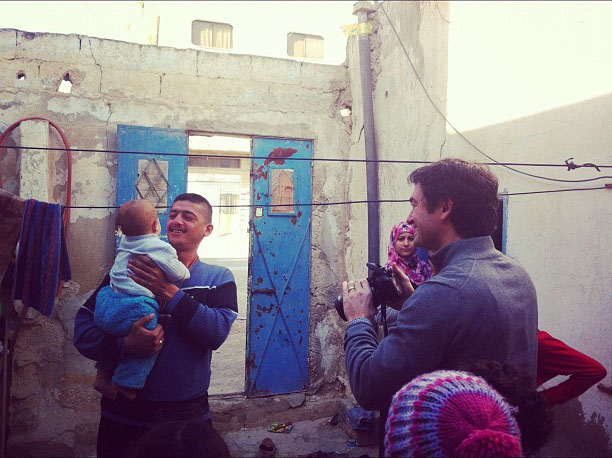

The Portland, Oregon-based Mercy Corps is on the ground in more than 40 countries, providing both short-term emergency assistance and long-term economic and community rebuilding. Barnicle is responsible for raising money from individual, foundation and corporate donors and communicating the work of the organization through the media and marketing campaigns.

“Our Syria work focuses mostly on alleviating suffering, which is a big part of our mission,” Barnicle said. “Syria is an example of what I refer to as the ‘hot humanitarian crises,’ which means situations where active conflict and huge displacement means we’re just trying to meet people’s basic human needs. Outside of those contexts, we’re trying to help fragile places become more resilient by mitigating conflict, building economic livelihoods, strengthening food systems, providing access to financial services and improving local governance.”

The focus of Mercy Corps’ work on the Syrian crisis is both inside the country and in Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq and Turkey. The declining media coverage of the civil war has had a negative impact on public interest, posing challenges to raising money specifically to meet the ongoing needs of Syrians caught in conflict. But the organization has assisted about 4 million refugees and internally displaced people with food, water, clothes, mattresses and shelter. Beyond that, they are supporting children’s recovery from their traumatic journeys and promoting overall development.

Overall, Barnicle and his team raised $60 million for Mercy Corps this past fiscal year from their work with individual donors to building partnerships with corporations such as Google and Coca-Cola.

Barnicle has been working on aid and policy issues since college. He graduated from Vanderbilt University with a bachelor’s degree in public policy and then joined the Peace Corps, which took him to western Hungary to teach English and to a community of Bosnian refugees at camps in the country. Before entering the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, he served jointly as a press officer for the U.S. State Department and Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe’s Mission to Bosnia and Herzegovina; was campaign manager and legislative assistant to Congressman Adam Smith (D-WA); and advised the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation on communications. He joined Mercy Corps 10 years ago, shortly after earning his MPA, and now serves on the Wilson School’s advisory council.

“The Wilson School was excellent preparation for what I wanted to do,” Barnicle said.

When he applied to the School, his intention was to learn how to effectively use resources from developed nations to advance the wellbeing of people living in underdeveloped regions, without ignoring the culture of the various societies.

He meets the challenges of his job overseeing resource development, marketing and communications with much of what he learned in the required MPA course “Psychology for Policy Analysis and Implementation.”

“Take complex, distant, hard-to-envision problems with imperfect solutions and try to get someone here in the U.S., today, to go online and give money to fund those solutions. To motivate people, they need to understand the problem and believe that their action – giving money, calling a member of Congress – is a meaningful part of the solution,” Barnicle said. “Then you have to make taking that action as easy as possible for people.”

The survivors he’s met motivate much of Barnicle’s work.

The survivors he’s met motivate much of Barnicle’s work.

In fall 2005, he was visiting a camp for those internally displaced by the war in Darfur during Ramadan.

“I was visiting with a widow with four or five young kids running around her dwelling – pretty much a hut with a U.N. tarp for a roof – and I asked her why Muslims fasted during Ramadan. She said, without a hint of irony, ‘Oh, we fast during Ramadan so we never forget what poor people go through,’” Barnicle said. “That this woman had the strength, resilience and dignity to feel that was an early important lesson for me in how much respect these people deserve.”

Barnicle's also witnessed first-hand what can spring from working directly with members of society on the use of the aid. After a devastating cyclone hit Myanmar in 2008, Barnicle was at a community meeting about the rebuilding infrastructure using funds from Mercy Corps. Those in attendance were each fervently defending their opinion on what the first step should be.

“I was struck,” Barnicle said. “This is what democracy looks like. For someone whose first passion was politics, it was amazing to see something I’d so taken for granted – the ability of neighbors to assemble and debate something – starting to take root where it hadn’t before.”

It’s possibilities like this that keep Barnicle, Mercy Corps and donors working to bridge funding to the perseverance of those in crisis. Even in the dire case of the Syrian conflict, sound strategy and communication are bringing relief to those suffering, starting with the click of a mouse.