Is China a rival super power to the U.S.? Is its rise a threat to U.S. leadership in Asia and beyond?

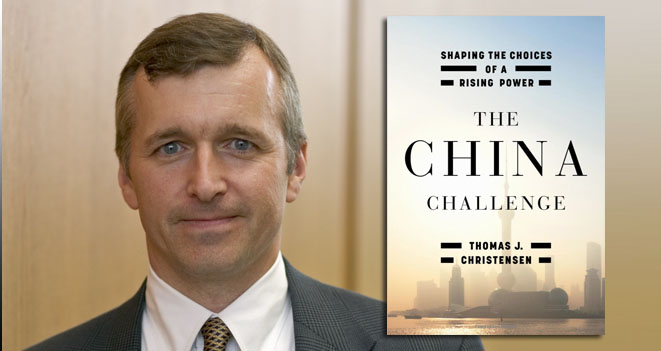

In his new book, Thomas J. Christensen, the William P. Boswell Professor of World Politics of Peace and War and director of Princeton-Harvard China and the World Program at the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, describes a new paradigm in which the real challenge lies in dissuading China from regional aggression while encouraging the country to contribute to the global order.

Drawing on decades of scholarship and experience as a senior diplomat, Christensen offers a new assessment of U.S.-China relations.

Christensen explores the origins of his book in the Q&A below. He will deliver a public lecture on Wednesday, Sept. 30, 4:30 p.m., Dodds Auditorium, Robertson Hall on the Princeton University campus.

Q. Why did you write this book?

Christensen: The rise of China poses some of the most important challenges to the United States, its allies and its security partners in the 21st century. In my opinion, those challenges have been routinely misunderstood and misconstrued in media and academic circles. I have studied China’s foreign relations as an academic, and I have worked on U.S. foreign policy toward China and East Asia as an official for the U.S. Department of State. I hope the book will convey to a broad readership some of the lessons I have learned.

Q. What are the biggest takeaways?

Christensen: There are two themes in the book. First, while China is nowhere near a peer competitor of the U.S. in terms of military, economic or diplomatic power, it is already strong enough to pose major problems for U.S. strategy. China’s rise can easily destabilize East Asia, where the U.S. has important interests, allies and security partners and where China has sovereignty disputes and other differences with several of its neighbors. China is projecting significant power offshore for the first time, and the combination of Beijing’s growing international confidence and domestic insecurity, particularly since the 2008 financial crisis, creates a difficult challenge for those trying to dissuade China from settling regional differences in a coercive manner. The second challenge is in the realm of global governance and is arguably more difficult to tackle. The world is more integrated than ever before and the solution to many problems – proliferation of nuclear weapons, financial instability, humanitarian disasters and regional instability and climate change – requires active contributions from all the great powers. But never before has there been a great power like China that also is a developing country; and never before has a developing country been asked to contribute so much to solve problems far from home. It does not help that the Chinese government has many domestic political, economic and social problems and has based its legitimacy in part on a form of postcolonial nationalism that treats with suspicion several of the others great powers seeking China’s greater cooperation.

Q. What are the policy implications in your book?

Christensen: The book outlines the successes and failures of former U.S. Presidents from George H.W. Bush to Barack Obama in tackling these twin challenges since the end of the Cold War. From that recent history, the book draws policy lessons on how best to dissuade a rising China from destabilizing East Asia and how to convince Beijing to contribute more actively to stabilize the international system from which China has benefited so much in the past four decades. While no one can dictate to Beijing what it must and must not do, foreign countries can shape the choices of a rising China so that it is more likely to seek national greatness through cooperation and less likely to solve its problems through coercion.