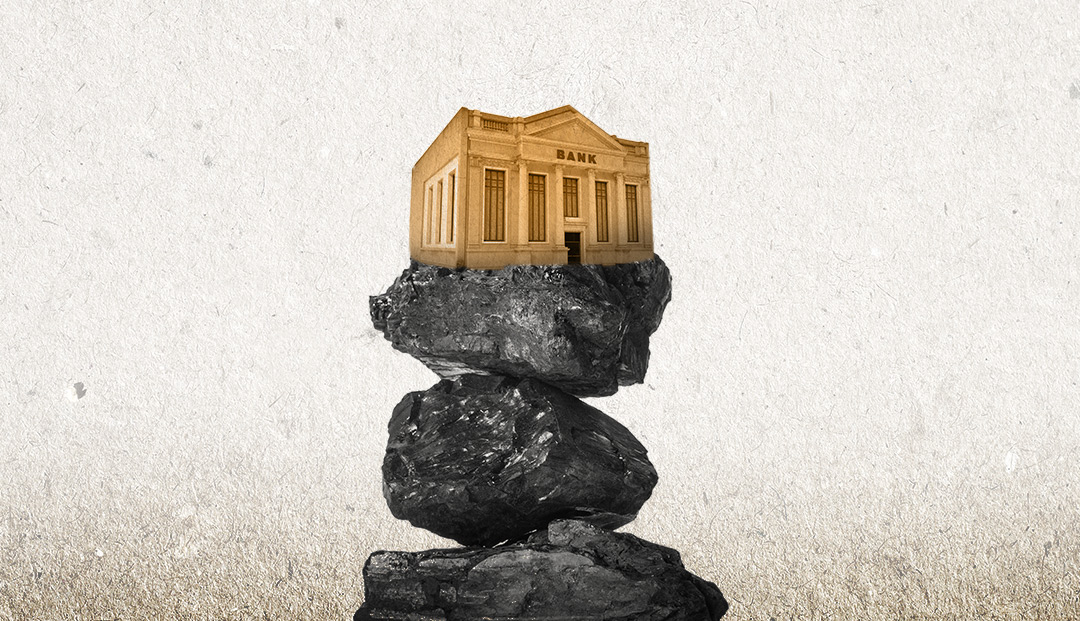

While the World Bank and other multilateral development banks are increasingly investing in renewable technologies and phasing out coal power financing, several of the world’s largest national-level funders — East Asian development finance institutions — are among the last public financiers supporting coal power plants.

An analysis led by Princeton researchers has for the first time quantified the contribution of these kinds of development finance institutions in China, Japan, and South Korea to global power infrastructure development.

The findings, based on the dataset the researchers constructed, indicate that the China Development Bank (CDB) and the Export-Import Bank of China (CHEXIM) have recently become the largest public financiers of the global power generation sector.

From 2006 to 2015, financing by these two banks resulted in more power plant capacity growth — particularly in coal, hydroelectric, and nuclear plant capacity — than the world’s ten major multilateral development banks’ public lending combined.

“China’s overseas development finance has greatly promoted power infrastructure development in the recipient countries,” said Xu Chen, lead author of the study and postgraduate research associate at Princeton University’s Center for Policy Research on Energy and the Environment. “However, it is important that Chinese and other East Asian financiers, as well as the recipient countries, take into account the climate risks of fossil fuel plants and consider renewable alternatives, especially as renewable energy becomes less costly than coal fired power generation.”

Development finance institutions are established by governments, either nationally or multilaterally with two or more countries, to fulfill public policy objectives identified by the funders, such as facilitating infrastructure development or trade with emerging markets. The availability of international financing for large-scale energy projects plays a significant role in shaping countries’ choices about what types of power plants to build, across fossil fuel and renewable options.

Given that fossil fuel power plants may operate for 40 years or longer over their lifetime, the fossil fuel-based power generation systems receiving funding and being built now will lock in significant greenhouse gas emissions for future decades. Of all power technologies available, coal-fired power plants are the most carbon-intensive and may also emit health-damaging air pollutants.

Current investments in coal power carry both serious climate risks and financial risks, since coal plants may be underutilized or decommissioned as emerging markets shift to more renewable energy. The researchers also found that compared with the multilateral development banks, coal plants financed by the national development finance institutions generally had less transparent and complete reporting of their equipment’s pollution control technologies.

“China has committed to reach carbon neutrality by 2060 domestically,” said Denise Mauzerall, professor of environmental engineering and international affairs at the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs and School of Engineering and Applied Science. “If it makes its foreign investments consistent with its domestic policy, Chinese development finance institutions could become a critical force in the international effort to decarbonize the global energy system.”

The data from this research and a related study by Princeton researchers have contributed to the development of an open-access, interactive data project — “China’s Global Power Database,” housed in the Boston University Global Development Policy Center at the Frederick S. Pardee School of Global Studies.

The authors are currently examining overseas financing of power plants from the United States and Japan in comparison with China. To rapidly decarbonize the global economy, domestic and international investments, including both multilateral and bilateral finance, will need to align with the Paris Agreement.

“Chinese Overseas Development Financing of Electric Power Generation: A Comparative Analysis” appeared first in One Earth on October 23, 2020. The authors are Xu Chen and Denise Mauzerall of Princeton University and Kevin Gallagher of Boston University, director of the Global Development Policy Center.

This study was supported by funding from the Center for Policy Research on Energy and the Environment at Princeton University, the Boston University Global Development Policy Center, the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation, ClimateWorks Foundation, and the Rockefeller Brothers Fund.