Justice Without Vengeance: A Princeton SPIA Researcher Seeks Answers When His Work Turns Personal

Laurence Ralph had been researching gang-affiliated young people for more than a dozen years when the topic landed on his doorstep with an urgency that no peer-reviewed paper could hope to match.

It was September 2019, and he had just learned that his stepson’s half-brother had been fatally shot in San Francisco.

Luis Alberto Quiñonez – known as Sito – was 19 when he was killed. The murderer was a 17-year-old named Julius Williams, whose brother had been stabbed to death by an acquaintance of Sito’s five years earlier.

The violent, tragic intersection of Ralph’s personal and professional lives touched him deeply.

“I had witnessed street violence while working in Chicago as an ethnographer, but my academic career was all about analyzing and dissecting trauma from a distance,” says Ralph, the William D. Zabel ’58 Professor of Human Rights and a professor of anthropology and SPIA associated faculty. “After Sito’s murder, I found it increasingly hard to be an objective third party to grief.”

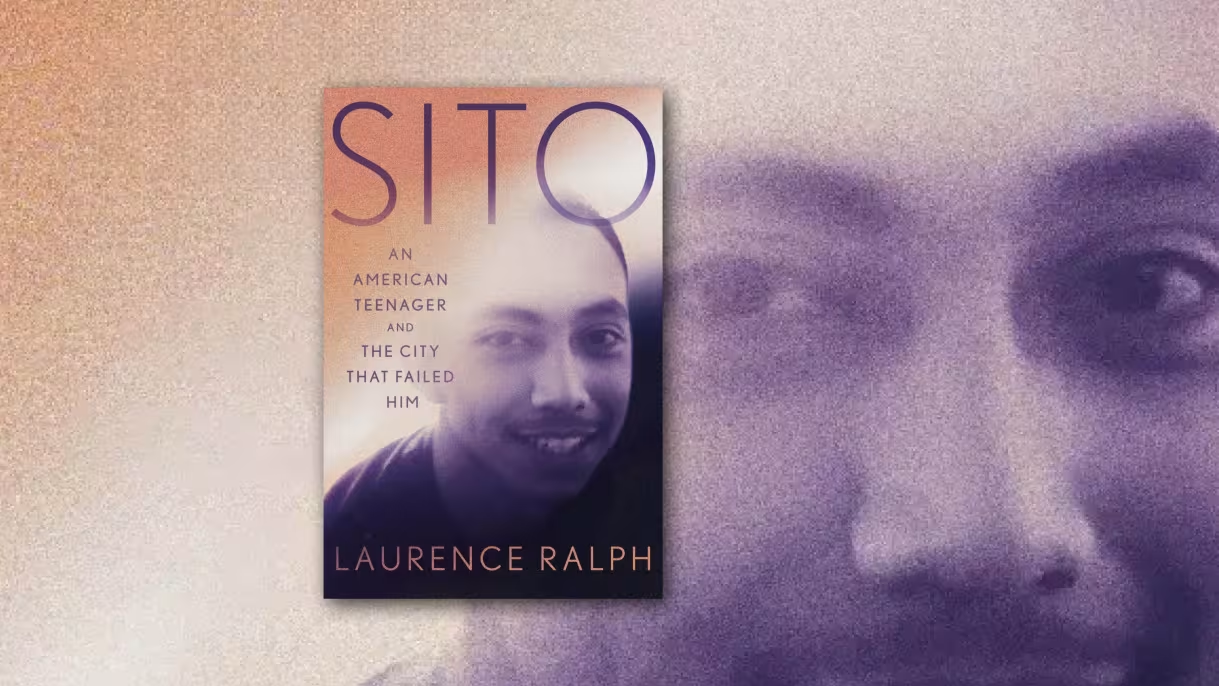

Ralph’s most recent book, “SITO: An American Teenager and the City That Failed Him” (Grand Central Publishing), is his attempt to find meaning in the tragedy. It is also the story of his personal struggle to find justice without vengeance.

“Many Black and Brown Americans live in constant fear of a loved one being injured, killed, or arrested,” he says. “They live one phone call away from having their lives changed by a violent crime, or by the callousness of the legal system itself. Writing the book about Sito became my window into this reality.

-----

Excerpt: “SITO: An American Teenager and the City That Failed Him”

For a long time, I thought my mission as a scholar was to prove that the so‑called bad kids weren’t born that way, so making a mistake should not scar them for life, crush all their prospects. I wanted my work to speak to the beauty and brilliance I sensed within the young people I was encountering at Cook County Juvenile. But perhaps my optimism was reflecting my own hopes, my own experience, not theirs. Back then I refused to accept—would not allow myself to believe—that their time in juvenile hall would follow those young men like a dark shadow, relentless and oppressive.

Did my research really reflect the hardships that those young men—those children—and their loved ones were living through?

Today, I can’t be sure.

Not until Sito’s murder did I entirely grasp how worthless a victim’s family can be made to feel in its encounter with the criminal justice system.

“The SFPD wants us to kill each other so they don’t have to,” Sito’s father, Rene, once said to me.

I understood that the prospect of seeing his son’s killer back on the street in five years (the limit for juveniles Julius’s age, according to California law) might seem like proof of that to Rene. I also knew that locking up a seventeen‑year‑old boy for the rest of his life was not going to solve anyone’s problems. And, as my stepson said, it wasn’t going to bring his brother back.

But in my heart, I shared their pain—and some of their rage. Sito’s family didn’t need structural analysis, or statistics. They didn’t need me to help them navigate the criminal justice system. They needed the system to respect them and to deliver justice. Only, in pursuit of that justice, they didn't want to become vengeful themselves. The problem was that having a child murdered does not incline a parent to calm, thoughtful reasoning.

James Baldwin wrote that “Hatred…never failed to destroy the man who hated.” Since the night my stepson called us with the tragic news, I have learned that the human being within the writer can only ever cope with grief through an intimate and introspective kind of empathy. My work on Sito’s case has been different than anything else I have undertaken. By researching and writing about his life and death, I hoped to add to the understanding of crime, violence, and injury—because that is what I do, it’s my profession, it’s my field. However, what I really needed to do—and what actually drove the research and the writing—was to help my own family heal, before the cycle of vengeance could claim another victim.

-----

Note: Ralph will serve as a participant in a roundtable discussion, “Writing Social Problems Through the Personal,” on February 28 at 11 a.m. in Maeder Hall. The other discussants are Angela Garcia, author of “The Way That Leads Among the Lost: Life, Death, and Hope in Mexico City’s Anexos”; Antonia Hylton, author of “Madness: Race and Insanity in a Jim Crow Asylum”; and Reuben Jonathan Miller, author of “Halfway Home: Race, Punishment, and the Afterlife of Mass Incarceration.” The moderator is Lucas Bessire, author of “Running Out: In Search of Water on the High Plains.”