Profiles in Perseverance: Living With Hope

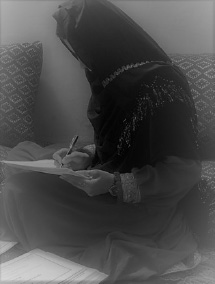

The Captivating Stories of Afghan Women Striving for Their Rights

To commemorate International Women’s Day, the Afghanistan Policy Lab profiled eight Afghan women, highlighting the struggle and the fight of women in the country. These profiles share the struggle of Afghan women to survive, to live and not give up their fight, and to hope. These courageous women write poignantly of the lives of Afghan women in the country today, when simply breathing is a struggle. APL dedicates this March 8 to all women in Afghanistan, and honors their struggle and fight, and to state that every Afghan woman in Afghanistan is a Hero!

The names below are pseudonyms in order to protect these women’s identities.

Twenty-two-year-old Ghotai was a second-year law faculty student in Nangarhar province when the Taliban took over the country in 2021. She studied for two more semesters under Taliban rule and was about to enter the third year when universities were closed for girls. But she did not quit. She continued her fight to live and remained hopeful, persisting in helping people in need.

Twenty-two-year-old Ghotai was a second-year law faculty student in Nangarhar province when the Taliban took over the country in 2021. She studied for two more semesters under Taliban rule and was about to enter the third year when universities were closed for girls. But she did not quit. She continued her fight to live and remained hopeful, persisting in helping people in need.

Ghotai continued her work as a civil activist, and consequently, she received many warnings from the Taliban to cease her activities. But she resisted and even ignored the calls she received from Taliban intelligence. The Taliban eventually raided Ghotai’s house and took her to a police security unit. They imprisoned her for about five hours, and finally, she was released through the mediation of the local elders with the promise that she would stop her work. Ghotai did not comply with the Taliban’s demand and remains engaged in working with the community. She is responsible for coordinating programs for “Khana/house,” a social organization.

Before the Taliban takeover, the organization raised awareness about violence against women, domestic violence reporting, and access to education for women and girls. It also provided relief to people in need. Its focus was on providing educational opportunities, particularly for orphaned girls and boys in Nangarhar province. With the Taliban in power, its activities have gradually been limited, and now it works only in delivering assistance to people in need.

In Afghanistan, and especially in the area where Ghotai lives, some families have not traditionally prioritized girls’ education. Realizing this, Ghotai worked to convince families to allow their daughters to study.

“There are families that say that a woman’s place is either in the house or in the grave. By launching a house-to-house campaign, we were talking to the fathers and brothers of these girls, so they would allow the women in their families to get an education. We wanted to convince them that their sensitivity toward girls’ education was incorrect. Many agreed to send their daughters to school after talking with us.”

When the Taliban took over, all the girls who enrolled in school with the help of Ghotai and her colleagues once again were forced to stay at home. Most of the Taliban leaders barre women from education based on their interpretation of Islamic teachings and they mention the environment not suitable for women to continue their education. However, they have not clarified what a completely Islamic environment means and when such settings will be available. In reality, their edicts are not based on Islam or Afghan values.

Many elders and ethnic influencers of the village support Ghotai, and their presence bolsters her in her activism. Ghotai frequently tells the story of being arrested by the Taliban, and how without the support of elders and local people, she would not have been able to move forward afterward. Yet there are many people who strongly oppose Ghotai’s activities.

“Some people believe that a woman’s place is at home, and that my deeds are not right. Thanks to the Almighty, I have local elders’ support. If it wasn’t for their help, I wouldn't be able to do my work.”

Although Ghotai’s parents did not finish school and only studied until the sixth grade, they always supported her and believed that she and other girls and women have the right to work and study.

Ghotai, who sometimes needs to leave her home, must take a family member with her because, according to her, the space for women in Jalalabad is so restricted that almost all women wear veils, or burqa, and must be accompanied by a Mahram, a male guardian. Recently, Taliban members from the Ministry of Vice and Virtue, came to Ghotai’s local mosque and warned residents that if their women left the house without a Mahram and burqa, the men of the family would be prosecuted. In the middle of 2022, the Taliban again announced that women must observe the hijab; if they do not, the family’s men will be punished.

Once when Ghotai wanted to attend a meeting organized by the International Organization for Migration, the Taliban was guarding the premises and prevented her from entering. She found this abhorrent, as she was attending an all-male meeting while observing a complete Islamic hijab. Such incidents have distressed Ghotai, who has cried silently and grieved for living in Afghanistan.

“Women right now in Afghanistan are oppressed, and there are times that I wish to despair as to why I was born a woman in this country.”

Twenty-nine-year-old Dr. Matina once wanted to be a broadcast journalist, but her family disapproved, and she was forced by her father to study midwifery and then the faculty of medical science. Today she is the coordinator of the midwifery program in Helmand province. She is satisfied with her work and is happy that she can save the lives of mothers and infants through her job.

Twenty-nine-year-old Dr. Matina once wanted to be a broadcast journalist, but her family disapproved, and she was forced by her father to study midwifery and then the faculty of medical science. Today she is the coordinator of the midwifery program in Helmand province. She is satisfied with her work and is happy that she can save the lives of mothers and infants through her job.

Until August 2021, Helmand was considered one of the most insecure provinces in Afghanistan. In 2005 and 2006, there was a resurgence of the Taliban in Helmand. Nadali district also gradually became insecure, and it was in 2007 that Matina’s father, who had a clinic and a pharmacy there, decided to move to the provincial capital so that his children could study in a relatively peaceful environment. Now under Taliban rule, the war and conflict have ended. Matina studied up to the eighth grade in the Nad Ali. After that, she was forced to move to Lashkargah, the capital of Helmand province, due to increased insecurity.

The training center that Matina now heads is funded by United Nations, and the project is run by an educational institute. According to the provisions of this institute, all girls and women who want to be enrolled in this two-year program must have completed 12th grade. However, this is not the case; some girls are functionally illiterate, and only two of the 32 girls currently in the program have graduated from high school. After joining the institute, the girls quickly learn to read and write. Besides midwifery, they also learn English and computing. This educational institute’s program is designed so that anyone who graduates from it is obliged to return to their village and continue their work as a midwife.

Although the Taliban have announced that women cannot work in non-governmental organizations, they have made some exceptions for the health sector. Matina does not hide the challenges of her employment — the Taliban have forced the midwives to travel with Mahram, male guardians, wherever they go. All 32 students have Mahram, and they live next to them. According to Matina, this has increased the service cost.

“Now, a man in the family must be free to accompany us. For instance, when I needed to go to one of the districts, I had to take my husband, who could hardly take leave from his office.”

Matina does not have a problem with the hijab mandated by the Taliban, which is the burqa. She has been wearing a burqa since she was 15, when she had just started studying midwifery.

“It’s hard for me to make eye contact with a stranger. However, I don’t have any problem in the workplace if I don’t have a burqa.”

Also, she is fine with the Taliban’s order to separate boys’ and girls’ classes in universities as long as girls are allowed to study. However, she thinks it is challenging because there must be enough female professors to teach female students, which is not the case.

Once upon a time, the radio was Matina’s companion. She kept the radio next to her ear at night, falling asleep with stories and soft songs from Radio Arman. She dreamed of hearing her voice on the radio one day, but the dream remained a dream. Since her family did not approve of their daughter’s voice being broadcast on the radio, she never tried to call the station or be a guest on one of the programs.

“I was 15 years old and in the 10th grade. My father insisted that I study midwifery. I had to study midwifery. On the first day, I started the practical work, I felt weak and passed out after seeing a child delivered.”

Matina became a midwife against her will, but now she said she feels satisfied and enjoys her work. When she helps a woman with a normal labor and delivery, she feels contented. “In the clinic where I was on duty, when I heard a child after the first cry, I had a sense of happiness and accomplishment. Now, as the head of the midwifery center, I am happy that we are training midwives who would go to the farthest areas of their provinces to save the lives of mothers and children,” she said.

Twenty-five-year-old Nilofar, a medical student, is forced to stay at home due to women’s education and employment bans by the Taliban. Last month, after waiting for a year and a half, she went to take the exit exam with the hope of getting her credentials. However, she and thousands of other girls were not permitted to take the exam. Nilofar returned home with tears in her eyes.

Twenty-five-year-old Nilofar, a medical student, is forced to stay at home due to women’s education and employment bans by the Taliban. Last month, after waiting for a year and a half, she went to take the exit exam with the hope of getting her credentials. However, she and thousands of other girls were not permitted to take the exam. Nilofar returned home with tears in her eyes.

According to Nilofar, among the 10,000 students in medical school, 3,000 were young women who were not permitted to sit for the final exam. The Afghan Medical Council has told Nilofar to wait “until further notice,” according to the order of the Ministry of Higher Education and Ministry of Public Health of the Taliban. All restrictions imposed by the Taliban upon her and women like her have been decreed until further notice.

The Taliban has often stated that an appropriate environment is not in place for girls to work and study, and until they create an “Islamic setting,” whose meaning no one understands, women should remain at home. Nilofar has obeyed this edict thus far, but she is concerned about the future. Focusing on her studies and preparing herself to eventually take and pass the exit exam has allowed Nilofar to overcome the boredom of remaining in place for the last two years. However, when she looks back at her efforts, anger and sorrow overwhelm her.

Nilofar, like thousands of other Afghan women, has not remained quiet; she speaks with other Afghan women as frequently as she can through online platforms, despite the restrictions imposed by the Taliban. Thanks to the internet and social networks, the information flow from Afghanistan has been uninterrupted, and people like Nilofar act as messengers, conveying to the outside world the terrible news of what is happening in their country. She participates in online meetings with other Afghan and foreign women worldwide, and she talks openly about the pain and suffering of Afghan women. It is helpful for her to share and connect in this way. It provides some catharsis for her, while also informing people across the world about the plight of women in Afghanistan.

Nilofar believes that women must talk to each other, which helps to strengthen them through their struggles.

“We are trying to keep women’s activism alive, albeit online. Our goal is to fight against the beliefs of the Taliban”

Nevertheless, fear follows Nilofar and other Afghan women as the Taliban silences any voice opposing their position. “We are afraid of even holding very private meetings, that the Taliban may come, and something may happen,” she said. Nilofar’s fears, of course, are justified. In November 2022, Zarifa Yaqoubi, a women’s rights activist in Kabul, along with many other Afghan women, was detained during a news conference in western Kabul.

Activism has been part of Nilofar’s life since she graduated from high school. She was a women’s rights activist while studying medical science before the Taliban’s takeover. She advocated for the inclusion of women in the government sector. With the help of other women activists, she has provided educational opportunities for orphaned girls. Now, all her work has been transferred to the online space.

Nilofar calls the silence of Afghan men against the bans on girls’ education and employment a disgrace.

“It is shameful that we [women] stand, protest and raise our voices, but no men support us. It’s as if they were waiting for the Taliban to regain power and tell women to stay at home. Whatever we do, at least they should stand with us, as the people of Iran did.”

The Taliban’s misogynistic actions have infuriated Nilofar. She misses the days when she and her classmates and friends celebrated each other’s birthdays, held get-togethers, and laughed. When she thinks of the limitations placed upon them, she prays from the bottom of her heart that the Taliban will fall again.

“I pray to God for a miracle — that when I sleep at night and wake up in the morning that the Taliban are gone. Sometimes, when we talk with friends, we pray to God to make America furious again with the Taliban.”

After the fall of Afghanistan, Nilofar’s father became seriously ill. He had a brain tumor and could not be treated in Afghanistan. He needed to travel to Pakistan or India for medical care, but unfortunately, his passport expired, and the Taliban had stopped issuing new ones. Sadly, he died as a result. This was the bitterest incident for Nilofar, as her father was always supportive of her. She now lives alone with her brother and mother.

“I will never accept the Taliban, I lost my dearest one because of them. I will not forgive them."

Despite all this, Nilofar asks other Afghan girls not to lose hope. “These struggles will pay off one day. It may not work for us now, but I am sure it will work for the next generations. We are currently in a situation where we have no choice but to fight. Education never loses its position,” she said.

Noorin was only a year old when the Taliban was driven out of Afghanistan by the United States and allies post-9/11. Upon the removal of the Taliban, a space had been opened where boys and girls could again attend schools and universities. The Rozi village in the Behsoud district of Maidan Wardak province, Noorin’s birthplace, is one of the most deprived places in Afghanistan. Students always had struggled to have access to educational materials, classrooms, or teachers. However, there was a thirst for education. Noorin studied in the first class held at her village, and then was forced to flee to Kabul because of a war between armed nomads and villagers. In Kabul, she dreamed big, worked hard and eventually achieved her first goal: She was accepted to the IT Department of Computer Science Faculty at Kabul University. On August 15, 2021, however, things suddenly turned for Noorin and her generation. The return of the Taliban on that date led to the collapse not only of the Afghan government, but of her dreams, as well.

Noorin was only a year old when the Taliban was driven out of Afghanistan by the United States and allies post-9/11. Upon the removal of the Taliban, a space had been opened where boys and girls could again attend schools and universities. The Rozi village in the Behsoud district of Maidan Wardak province, Noorin’s birthplace, is one of the most deprived places in Afghanistan. Students always had struggled to have access to educational materials, classrooms, or teachers. However, there was a thirst for education. Noorin studied in the first class held at her village, and then was forced to flee to Kabul because of a war between armed nomads and villagers. In Kabul, she dreamed big, worked hard and eventually achieved her first goal: She was accepted to the IT Department of Computer Science Faculty at Kabul University. On August 15, 2021, however, things suddenly turned for Noorin and her generation. The return of the Taliban on that date led to the collapse not only of the Afghan government, but of her dreams, as well.

For Noorin, the fall of Kabul was the end of her dreams, but not the end of her fight. In fact, the situation gave her the opportunity to actualize her hidden potential. She has made it her mission to support girls’ online study since the Taliban ban on education, and she began providing technological support to girls’ online education platforms. According to the World Bank, 18% of Afghanistan's population has Internet access. Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, Telegram, WhatsApp, and Instagram are among the most popular social media applications in the country. Noorin uses these platforms to counter the restrictions imposed by the Taliban. She is now an active member of several national and international social organizations and, through her example, she is providing a source of inspiration for other Afghan girls and women. She intends to become a human rights defender, working for UNESCO, and eventually hopes to become the Minister of Technology and Information in Afghanistan, when women will be allowed to work and be free.

Noorin is currently an active member of an international organization helping girls’ education. She leads a group of 25 Afghan girls living in different countries, including Afghanistan, Ghana, Nigeria, Nepal, and Kenya. Through this program, Afghan girls learn advanced English, job skills, and mathematics. She is a member of several national and international organizations. She participated in the activities of the Friday for the Future movement and the Pen Path education campaign. Now that she no longer can work outside the home, she has begun knitting and selling handicrafts to make a living.

For Noorin, August 15 is a sinister date. On August 15, 2018, while she was sitting in her class listening to the teacher, a suicide bomber attacked the class next to hers at Mouood educational center in Kabul. That attack left 50 dead and 70 injured. Afterward, the center suspended its activity. It eventually resumed under a different name — Kaaj, or pine tree. The Kaaj educational center suffered the same fate as its former iteration. In an attack on Kaaj that took place on Sept. 30, 2022, 53 students were killed, and 110 others were injured. The trauma that Noorin experienced was profound.

As someone who understands the social and economic structure of Afghanistan, Noorin said she believes that providing online education for Afghan women and girls is important in the short term, in the sense that doing anything is better than doing nothing. But it is not the long-term solution, she said.

When the Taliban seized Kabul in 2021, their first action against women was to terminate female employees from the government. That was when Rahima realized she had difficult days and challenging tasks ahead of her. She was one of the first women who took to the streets and chanted in opposition to the Taliban’s misogynistic actions. She played a role in establishing the Afghan women’s movement. During these past two years, Rahima has kept her voice raised against the Taliban. She now supports about 300 girls who have been denied an education through underground educational centers that she created with the help of other activist women.

When the Taliban seized Kabul in 2021, their first action against women was to terminate female employees from the government. That was when Rahima realized she had difficult days and challenging tasks ahead of her. She was one of the first women who took to the streets and chanted in opposition to the Taliban’s misogynistic actions. She played a role in establishing the Afghan women’s movement. During these past two years, Rahima has kept her voice raised against the Taliban. She now supports about 300 girls who have been denied an education through underground educational centers that she created with the help of other activist women.

The Taliban’s early edicts closing schools for girls remain indelible in Rahima’s mind. She remembers the days when most girls came to school early in the morning, eager to attend their classes. When the schools were shut down, those same students returned home in tears after facing closed gates. The memory remains one of the most tragic and bitter of Rahima’s life. That day, Rahima said, she felt overwhelmed with anger and hatred — she could not vent her strong feelings except by going into the street and yelling. The next day, she and a group of students took to the road and chanted against the Taliban’s decision. Their call was met with suppression and violence. In August 2022, Rahima launched a movement with the slogan “bread, education, and work.” The Taliban quelled those protests, as well, but the women refused to be silent, resisting the repressive measures by changing their approach.

Rahima is now educating girls above the sixth grade in underground educational centers. “Quitting her teaching position in a public school five months ago, she decided to take matters into her own hands and launched a covert educational program for the young girls.” Rahima, a chemistry and biology teacher, teaches academic subjects, as well as sewing and embroidery, to 50 girls in two shifts, morning and afternoon. She established a network of teachers, each of whom teaches about 15 to 20 girls in their homes. In those groups, the girls are asked to assist one another with skills including sewing, embroidery, and painting.

There have been challenges along the way. On the first day, many of the girls were severely mentally stressed because they had been away from their classes and classmates for a long time. According to Rahima, most suffered from depression. However, their condition has improved through psychotherapy sessions, which are offered online to the students. “The girls are happier now because they are studying and learning. I tell my students the schools may reopen this year. If not this year, then next year, you will be promoted to higher classes,” Rahima said.

Rahima is still determining whether she can continue to run the underground education centers due to economic problems. Due to an insufficient budget, it has been several months since the teachers’ wages have been paid. Many of the teachers have already informed her they cannot continue teaching without receiving salaries, although they are committed to the cause and find the work rewarding.

“I have created educational centers in the teachers’ homes without paying them the rent for three months. I told them I would pay their rent and salary after three months. Three months passed, but I couldn’t keep my word. Most teachers understand the situation, and they are continuing their work.”

Rahima recalls how she herself suffered grievously during the Taliban’s first rule. Her husband was killed in Kunduz during a Taliban attack on the province. She married her brother-in-law and had to leave with him for Pakistan. When the Taliban fell, they returned to Afghanistan. That was when she began teaching in public schools, attended university, and graduated from the science faculty. But tragedy befell her once again in 2017, when Rahima lost her son during a Taliban insurgence.

Rahima continues her fight against the Taliban in memory of her husband and son. In response to what keeps her continuing her work, she said,

“When people do not support a government, it falls apart. I am 52 years old, and many governments have ruled and fallen apart. None lasted because they never had public support. The Taliban’s regime will fall apart one day. We must be prepared for tomorrow, and our girls must be prepared to go to school.”

Roya was born in one of the villages of Ghazni province in 2003. Her father, concerned about his children’s education, moved the family from their village to Herat. Besides studying, Roya played sports in Herat. She dreamed of playing on Afghanistan’s national women’s volleyball team, which she eventually was able to do. She planned to become a doctor while continuing to shine on the national team, but then, the government of the Islamic Republic collapsed. With the departure of the last American military plane from Kabul Airport on Aug. 31, 2021, her aspirations seemed to depart, as well. But Roya did not succumb to her situation. Despite being forced to stay at home, she has continued to plan for her future.

Roya was born in one of the villages of Ghazni province in 2003. Her father, concerned about his children’s education, moved the family from their village to Herat. Besides studying, Roya played sports in Herat. She dreamed of playing on Afghanistan’s national women’s volleyball team, which she eventually was able to do. She planned to become a doctor while continuing to shine on the national team, but then, the government of the Islamic Republic collapsed. With the departure of the last American military plane from Kabul Airport on Aug. 31, 2021, her aspirations seemed to depart, as well. But Roya did not succumb to her situation. Despite being forced to stay at home, she has continued to plan for her future.

Even before the government’s collapse, girls’ sports were considered taboo in Afghan society. Girls, including Roya, fought their families and communities to maintain the right to play. Roya started playing volleyball in ninth grade, and after working hard, she made it to the national team. She was supposed to attend competitions abroad, but when the Taliban regained power, girls’ sports were banned entirely. Her dream of playing for her country and winning honors for Afghanistan became impossible. Roya asks why sports are allowed for men but not women, arguing that both genders have bodies made for activity with the same joints, bones, muscles, and heart. The Taliban oppose such arguments, holding that sports are incompatible with Islamic and Afghan values for women.

In all other Islamic countries except Afghanistan, women have the right to education and employment. In fact, the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) has condemned the Taliban’s prohibitions on girls and women. Roya traveled to Iran for a while to continue her education; however, she could not attend the university there because she did not have a high school certificate. Before the return of the Taliban, Roya had just graduated from 12th grade, and though she had fulfilled all of her requirements, she was prevented from receiving her diploma. Even still, she has not given up on her dreams. Currently, she is learning English online and preparing for scholarships in different countries where a high school certificate may not be necessary. She applied to a university in Bangladesh, passed the interview, and is awaiting final word. Even if she receives a scholarship in another country, she will face additional barriers. She may not be able to travel due to the Taliban ban on women’s travel. She also fears the Taliban will not allow her to depart from the airport. In August 2022, a group of female students from the American University of Afghanistan was prevented from leaving Kabul Airport. With all the restrictions and mental pressure she endures, her family’s support and the hope she holds for her own future have kept her motivated.

A day before Herat fell to the Taliban, Roya’s family moved to Kabul, hoping that the city would not fall easily and that they might live in a safe environment for a while. However, only two days after their arrival, Kabul also fell. The situation in the city was chaotic from Aug. 15 to 31, 2021, when the last American soldier left Afghanistan. Roya was among the hundreds of thousands of people who rushed to the Kabul Airport and the borders of Afghanistan to flee the country. When she arrived at the airport, which was still in the hands of the American forces, she realized that it was impossible to pass the gate through the enormous crowd. The sounds of crying, screaming, and shooting remain in her mind from that day. She returned home disappointed. The day after the last American military plane left Afghanistan, the city was plunged into fear and silence. That day Roya said she became overwhelmed by despair and hopelessness. She slowly understood that the government had fallen. Roya said she especially misses her friends and has not seen them for a long time.

“The presence of foreign [American] forces was promising for us. When they left, we knew that we had come under the control of the Taliban.”

Twenty-nine-year-old Sahar — which means “just before dawn” in Arabic — is a herald of freedom and a bright light to her students. She works at a private school in Herat, teaching chemistry to girls in grades 7 through 12 and motivating them to stay the course with their studies. In a situation where women have lost the right to work, Sahar takes a risk showing up for class, teaching even on days when she is seriously ill, so that her students stay engaged and encouraged.

Twenty-nine-year-old Sahar — which means “just before dawn” in Arabic — is a herald of freedom and a bright light to her students. She works at a private school in Herat, teaching chemistry to girls in grades 7 through 12 and motivating them to stay the course with their studies. In a situation where women have lost the right to work, Sahar takes a risk showing up for class, teaching even on days when she is seriously ill, so that her students stay engaged and encouraged.

After the United States and its allies overthrew the Taliban government in October 2001, many Afghans who migrated due to civil wars in the 1990s returned home in the hopes that the country was headed in the right direction. Sahar’s family also returned from Germany to Herat when they saw on television that the Taliban had been overthrown after five years of rule. Sahar was 11 years old at the time. She studied through the fifth grade while living in Annenberg-Buchholz, Germany, but when she returned to Herat, it was immediately clear that she entered an education system of a far lower quality.

There was significant violence in Afghan schools, and harsh discipline. Having received a quality education in Germany, entering a substandard system was painful for Sahar, and she soon became depressed. She took the sixth-grade exam and was promoted to seventh grade. That year was when she decided to become a teacher — and one who was especially committed to her students. When Sahar was younger, she had been very interested in and demonstrated a high aptitude for mathematics. In fact, as a fourth-grade student, she was transferred to an advanced class due to her incredible talent in math. When she reached the 11th grade, she met a skilled and kind Afghan chemistry teacher who reminded her of her teachers in Germany. Her interest in chemistry bloomed as a result and set her upon her career path. She has since become the endearing teacher she once dreamed of being to her students.

Sahar has dedicated herself to promoting quality education for Afghan students so that sound pedagogy can spread across the country, improving the entire education system. With the Taliban’s takeover, Sahar’s classes are facing extreme challenges. Today, her primary concern is how to best motivate female students who have been severely affected by the Taliban’s restrictions on women.

Since the Taliban regained their rule in 2021, 80% of female students have lost the motivation to study, Sahar said. Overall enrollment also has dropped. The number of students in the school where Sahar teaches was 1,600 prior to the Taliban’s return; it is now 600.

“Many of our students migrated to neighboring countries just to study. In previous years, the teachers were all focused on educating the students, but this year, all of our efforts are focused on preventing our students from dropping out.”

To make classes more enticing for her students, Sahar has adopted new teaching methods, including combining lessons with games. Sahar does what she can to keep her female students from losing hope.

Since the Taliban regained power and deprived girls of an education, underage marriages have increased. Sahar tells the story of one of her 10th-grade students who called her to express her concern that she might soon become a bride against her will.

“Some time ago, one of my students told me that if the schools are not officially opened, the possibility that she would be forced to marry her cousin was very high. At the same time, I noticed that four of our 10th-grade students got married,” Sahar said.

According to Sahar, families believe that by marrying off their young daughters, they can assure that their lives are busy and prevent them from succumbing to mental illness caused by their lack of opportunity for study and work.

Several months after the Taliban was reinstated, some Taliban members attacked the school where Sahar was teaching and violently gathered all the officials and teachers. In a commanding tone, the aggressors asked school officials why, contrary to the decision of the Ministry of Education of the Taliban, they were teaching girls above the sixth grade. The school’s principal told the Taliban that it was not a school, but a training course. The Taliban stood down that day without physically harming the students or school officials. These threats, along with the restrictions imposed on women’s work and education, have demotivated most of Sahar’s female students. “Our students are all heartbroken — when I go to class, everyone expresses frustration,” she said.

“They ask why we should study when there is no hope for the future, but I do my best to motivate them.”

Although Afghanistan has become a prison for Afghan women under Taliban rule, Sahar said she is happy and enjoys being able to teach. She loves her work. During the past few months, she fell seriously ill twice. Still, she attended class with special measures in place, wearing several layers of masks so as not to infect her students. “I was told not to come to school until my recovery, but I could not bear to be away from my students,” she said.

Sahar advises her students to study in any way possible, regardless of whether they immediately can earn a degree. She believes that Taliban rule will eventually end, and that students who have studied will someday be able to take exams and enter higher classes after the Taliban are overthrown. According to Sahar, online resources have enabled students to learn in the interim.

“People are frustrated with the Taliban and have no interest in how they rule. When there is no support from the people, the government must adjust according to their will, or it will fall apart. If this situation continues for another year or two, the Taliban will fall.”

Sahar is especially worried for her daughter, who just finished the fourth grade this year. She said she wishes that her daughter was younger so that by the time she reaches sixth grade, the situation will have improved, and she can continue her education. “Sometimes I wish that my daughter was in the second or third grade,” I have fear in my heart for her. Let’s see if she can continue her education in the next two years when she finishes fifth and sixth grade. I do not know.” she said.

The Taliban have banned schools for girls above the sixth grade. However, in a few districts and provinces, places either under the name of “training centers” or in hiding are trying to continue to teach. There is no guarantee either of their safety or of how long these centers/schools can continue.

Before the Taliban’s arrival, 29-year-old Uzma graduated from the Faculty of Sharia of Kabul University and received her master’s degree in international relations from a private university. She took bachelor’s and master’s courses in the evening and was usually dismissed from classes at eight o'clock at night. At that time, she traveled home alone without any fear. In fact, during the seven years, she went home alone at night, she never faced any problems. Now that the freedom to travel by herself at any time has disappeared under the Taliban, she rarely leaves the house, and even on occasions when she does venture out, she does so in fear. Since Aug. 15, 2021, Uzma compares herself to a bird trapped in a cage. The cage that becomes narrower daily.

Before the Taliban’s arrival, Uzma and her friends often planned vacations to neighboring countries at the end of the year. She has visited Pakistan several times, India twice, Sri Lanka once, and Uzbekistan once. Every time she traveled, she did so unaccompanied and without any trouble. Now, according to the Taliban leadership, a woman can no longer travel more than 43 miles without Mahram, a male guardian.

Uzma works at an international humanitarian organization, as a supervisor of two educational and humanitarian assistance programs. Since December 2022, when the Taliban banned women’s work in humanitarian organizations, Uzma has been working from home. This ban has impacted the overall activities of these organizations, and most of their projects have been halted.

Like other women who know the value of life and liberty, Uzma works to enhance freedom for herself and others. She calls the continuation of her work, albeit online, a form of resistance against the Taliban repression: “I will continue until I can no longer continue,” she said.

Uzma started a small business in 2020, which ceased operation after the Taliban takeover. With the help of her female employees, she sewed Afghan clothes and sold them online. She now plans to resume her business.

For Uzma, thinking about the uncertain future for her sisters has caused her more pain than having to stay at home herself. One of her sisters was a university student, and the other attended school. Due to the restrictions imposed by the Taliban on girls’ education, they have stayed at home and are under severe psychological strain.

“The thought of my sisters has occupied my mind. I wanted to find online English classes for them, but no regular ones exist. Then I wanted to find a sewing course for them to stay busy, which is not the case, either.”

As a student of Sharia law, Uzma is well acquainted with what rights Islam grants to women. In her mind, the Taliban’s actions defy Islam because, according to the religion, there is no discrimination between men and women in education and work. Education is divinely ordained for both men and women.

“I studied Sharia for four years at Kabul University — for me, how the Taliban treat women is unacceptable.”

Uzma, who has examined the trajectory of restrictions imposed on women by the Taliban, said she does not feel confident that the situation will improve. She is worried the Taliban will soon announce that women do not have the right to go out of the house even to buy food and clothes — the only thing they are allowed to do at present outside the home. “We used to be able to go to women’s outing places, but now we can’t go anywhere. I’m afraid the Taliban will not let us leave the house soon,” she said.

Uzma fears facing a similar situation to the one she experienced when the Taliban were first in power. In 2000, when Uzma’s family returned to Afghanistan from Pakistan, the women in her family were beaten by the Taliban because they did not have a chadari, or burqa. That image is still vivid in Uzma’s thoughts. Now, when she hears the Taliban’s decrees against women, she fears she will be beaten like her mother for not wearing a burqa.

After the Taliban seized the country, most of Uzma’s friends left Afghanistan. When she tells stories with her friends, the stories are from the past and often end in despair. Now there is no possibility of their planning to visit a nearby country for a year-end vacation. The Taliban have stolen that opportunity from them and imprisoned them in their homes.

Uzma grew up in a family where boys and girls had equal rights. The Taliban regime, however, deprived girls of all rights, even against the wishes of their families. The restrictions they have imposed have impacted Uzma so deeply that she said she wishes she would not have been born a girl in a country like Afghanistan.

“I am stressed enough. Sometimes I cry and curse my bad luck, and I wish I would not have been born a girl in Afghanistan.”

But her fight for survival continues despite the despair.