Health care in America is expensive, but it doesn’t have to be, according to the late Uwe Reinhardt, former James Madison Professor of Political Economy and Professor of Economics at Princeton University.

A leader in health care policy, Reinhardt provides an incisive look at the American health care system in a new book, “Priced Out: The Economic and Ethical Costs of American Health Care,” published by Princeton University Press.

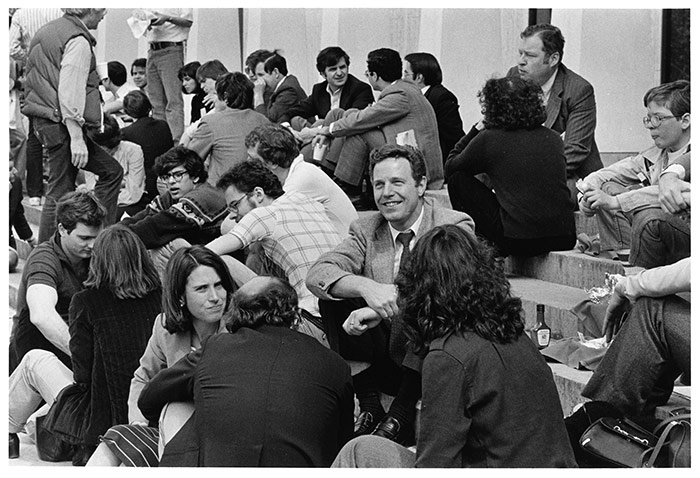

Reinhardt taught at Princeton’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs and Department of Economics for nearly 50 years. Throughout his career, he strongly influenced American health care, serving as an adviser to the White House and other governments.

In the Q&A below, his wife, Tsung-Mei Cheng, answers questions about the book.

Q. Why did Uwe write this book?

Cheng: For many years, Uwe wanted to write a book on health care for the American public and policymakers to explain the U.S. health care system, which is “so complex that it is often beyond human comprehension,” and our national health policy, which is “a bundle of confusion and contradictions.” He wanted a book to explain “the bizarre quirks” in our health care system that are unique to the United States, why health care is so expensive, who actually pays for health care in the U.S. He also wanted to explore whether, from an international perspective, Americans get adequate value for high health spending. He also wanted a book to rid the ignorance and dispel the misinformation, myths, and confusion about the U.S. health care system.

In another sense, the book can be said to be Uwe’s response to a long-held “popular demand” for such a book by him. Over the years, many people had urged Uwe, as a “listened-to voice on health care policy,” to write a book about American health care. Uwe’s unique gift to teach and communicate was widely recognized and sought after. Many also called Uwe a moral conscience of U.S. health care policy. People have told me they would read anything Uwe wrote. A former Princeton student once told me he took every course, graduate and undergraduate, Uwe taught at Princeton just to learn from him. So, ever the teacher, Uwe decided to take the classroom to the American public and policymakers.

With Uwe’s vintage sense of humor and irony, he titled his original manuscript: “A Visual Stroll through America’s Health Care Wonderland,” with lots of illustrations and supporting documentations.

Why the book now? Uwe worried about U.S. health care for decades, especially the problems of cost and the uninsured. He worried for this reason: “Even 20 years ago, it should have been clear that the collision of two powerful, long-term trends in our economy would eventually drive the debate on U.S. health policy to the impasse it reached in 2017. Indeed, some of us had predicted it years ago. ... The debate is conducted in the jargon of economics and constitutional federal-state relations. But it is not really about economics and the Constitution at all. Instead, at the heart of the debate is a long-simmering argument over the following question on distributive social ethics: “To what extent should the better-off members of society be made to be their poorer and sick brothers’ and sisters’ keepers in health care?”

Uwe describes what the two “ominous long-term trends” on which he based his “dire prognosis on the uninsured in the U.S.” are: first, the rapid growth in the cost of American health care in the face of, second, the growing inequality in the distribution of income and wealth in the U.S. Poignantly, Uwe points out that “over time, these two trends have combined to price a growing number of American families out of the high quality or at least luxurious American health care that Americans in the higher strata of the nation’s income distribution would like for themselves. We have now reached a pass where bestowing on a low-income American even standard medical procedures, such as a coronary bypass or a hip replacement, is the financial equivalent of bestowing on a poor person a fully loaded Mercedes Benz.”

The catalyst for Uwe’s decision to write this book, and the way he organized it, I believe, was the drama that was playing out in the national health reform arena in 2017. Then, there were several Congressional health reform proposals to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare). I think Uwe became very concerned about the impact of the Congressional plans, if passed (one did pass the House of Representatives), on the finances of American families and on the health and wellbeing of uninsured and underinsured Americans. Uwe thought many aspects of Obamacare need to be fixed — he describes how to fix Obamacare in the book — but he worried that doing away with it would cause many more millions of Americans to become uninsured and still millions more unable to afford needed health care even if they are insured.

I think that is why Uwe devoted the second part of the book to “the ethical questions” that the then “current situation [which remains current today] raises for health policymakers.” He wanted Americans to understand the “different distributive ethics different nations impose on their health systems and how the U.S. is different from the majority of the rich nations in Europe and Asia in that it has never been able to reach a politically dominant consensus on a distributive ethic for American health care.” In part two of the book, Uwe walks readers through the details of proposed reform plans, moot as of late 2017, to show “the estimated impact of the bill on American families,” and how “these details convey the general thrust of the debate and, in particular, the ethical vision baked into them.” Uwe, the teacher, wanted to help Americans make sense of complicated and jargon-laden legislative proposals.

Uwe hoped that in helping Americans understand our hugely complex health care system, they will become informed voters and consumers of health care, and participate in constructive ways in our ongoing national conversation on health care reform.

In some ways, this book was deeply personal. Uwe knew what it meant to be poor as he was once poor in post-war Germany and later a poor lone teenage immigrant in Montreal, where he landed with $90 in his pocket, having fled Germany because he “refused to salute German generals.” Countless times Uwe talked about how, despite the poverty, hunger, and physical hardships in Germany, he and his family had health insurance without which he might not have survived childhood – the many infectious diseases he contracted; wounds; and injuries sustained from playing with live ammunitions found in the field! Countless times Uwe told the story, as he did on NPR’s Fresh Air once: “I grew up in a toolshed, and I know how good it was when we were paupers, my family, we had health insurance like everyone else in Germany. I’ve never forgotten that. And I would like American people to have what I had and my mother had as a kid. So, that is why I care.”

Q. What are the biggest takeaways?

Cheng: There are a number of takeaways in the book, including:

- The United States is the most expensive health care system in the world. We spend 18% of our GDP on health care compared to average of 8.9% of GDP for countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in 2017. Per capita, the U.S. spent more than $10,000 in 2017 compared to the OECD average of $3,992.

- The high cost of American health care has priced out tens of millions of Americans from needed health care. Before Obamacare, we had around 40 to 45 million Americans without health insurance. Whether they received health care was based not on their health care needs but on their ability to pay. For poor people, that usually meant they went without needed health care. Uwe said that “our health insurance markets ration by price and income.” Obamacare reduced the number of uninsured in America but did not eliminate the problem. As of 2016, we still had some 27 million uninsured, and that number has climbed since.

- We are the only nation in the developed world that does not have health insurance for everyone despite spending much, much more than every other rich nation on health care.

- We also have tens of millions of Americans who are underinsured, and, as a result, they cannot afford to access the care they need either because their particular insurance plans do not cover the services they need, or because of the high deductibles and copayments. A familiar example is the high prices of prescription drugs that effectively prevent millions of Americans from getting needed medicines.

- Despite spending the most among rich nations on health care, Americans in fact neither a) get more health care — citizens in rich European and Asian nations often get far more care than Americans do — Uwe often said that “they eat more pills, and have more hospitalizations, etc.”, nor b) are healthier than citizens in many other countries that spend a lot less.

These takeaways are merely symptoms, or consequences, of a dysfunctional health care system that has failed large numbers of Americans. I cannot tell you how many times I had heard Uwe say the following, which to me are the two biggest takeaways of his book:

First, and the most important takeaway, is that we Americans have not agreed on what Uwe called “the distributive social ethics most nations seek to impose on their health systems,” and therefore begot the hugely expensive and chaotic health care system we have. Uwe explains this in the book:

Health reformers in Europe, Canada, or say, Taiwan (which operates a government-run single-payer system) usually began their debates on health reform by making explicit the ethical principles that should constrain their health policy. In Germany, for example, policymakers frequently recite the principle of solidarity. Canada’s Royal Commission report on the future of Canadian health care (2002) is titled, “Building on Values: The Future of Health Care in Canada,” and explicitly states what those ethical values are. For reasons that escape me, Americans typically shy away from an explicit statement on social ethics in debating health reform. Instead, that debate is couched mainly in terms of technical parameters like actuarially fair versus community-rated premiums, deductibles, coinsurance, maximum risk exposure, high-risk pools, and so on. ...

By contrast, we in the United States have never reached a politically dominant consensus on the issue. We debate these ethical issues only in camouflaged form. The debate in recent years on repealing and replacing Obamacare is merely a continuation of this camouflaged and confusing debate. However, one can infer from actual health reform plans the ethical platform on which they rest.

My personal experience is that merely bringing up the topic of distributive ethics for health care can easily raise the ire of an audience, because it is viewed as “too personal,” “too political,” and “too divisive.” Instead, we prefer to discuss health reform mainly in technical terms — usually economic terms — and let social ethics fall where they may.

To illustrate this point I cite an article I published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) in 1997, after the spectacular failure of the Clinton Health Reform Plan. The article was entitled “Wanted: A Clearly Articulated Social Ethic for American Health Care.” In its opening paragraph, I raised the simple question: As a matter of national policy, and to the extent that a nation’s health system can make it possible, should the child of a poor American family have the same chance of avoiding preventable illness or of being cured from a given illness as does the child of a rich American family?

University of Chicago Distinguished Law Professor Richard Epstein used a solidly Libertarian theory of justice to answer my question with a clear no. So charmed was I by this forthright response, I arranged a debate with him before some 500 University of Chicago students and faculty, followed by a cordial lunch from which we departed as friends who respectfully agreed to disagree with each other.

The second fundamental and sad truth or takeaway about our health care is that, in Uwe’s own words, “the issue of universal coverage is not a matter of economics. Little more than one percent of GDP assigned to health care could cover all. It is a matter of soul.” Yes, in America we have “brutal rationing [of health care] by price and income for the uninsured.” We could do much better for little additional money for those fellow Americans who need help.

Q. What are the policy implications?

Cheng: Health care has been, is, and will remain a top concern for Americans and our health policymakers for the foreseeable future. This is especially true as we head into the 2020 elections, which could give us a window of opportunity to make meaningful health reforms happen.

Now is the time Americans should decide if we want to remain the only rich nation that does not have health insurance for all. Given that the U.S. has the highest income inequality among OECD nations, it is urgent that we take actions to make our country a kinder home to all Americans.

Concrete reforms may include fixing Obamacare, as covered in Uwe’s book. Obamacare has gained popularity among Americans since failed Republican attempts to repeal and replace it. We know that people everywhere value health insurance — financial protection from the cost of illness. At the same time, we should seek solutions to the myriad problems in our health care system such as ways to expand health insurance coverage, make health care more affordable by controlling costs including high prescription drug prices and such capricious threats as surprise medical bills, payment reforms that give us greater value for what we are spending in terms of better quality and outcomes, etc.

I personally think Uwe’s own novel reform proposal is worthy of serious consideration by the American public and policymakers. The proposal’s main objective is for the United States to finally achieve universal health insurance for all Americans. Uwe strongly believed that health care is a public good and not a private consumption good, that every American should have access to needed health care. He said, “Let us focus on the bottom tier and say ‘let us make it good enough that, as Americans, we could be proud of it.’ I think that could be done.” Rich Americans, Uwe believed, can have whatever health care they desire regardless of how much it costs as long as they pay for it themselves and not with taxpayers’ dollars.

Uwe’s own proposal? In a clear-cut and honest way, Uwe proposes that “by age 26 all Americans must choose to either a) join an insurance arrangement that forces on them community-rated premiums [premium not based on health status] or, alternatively, b) take a chance on being uninsured or rely on a health insurance market with premiums based on the individual’s health status. If they chose the rugged individualist route, however, they could never later on join the social solidarity pool. They would be on their own throughout their life. That scheme would accommodate Libertarians who do not wish to be told by the government what to do about their health insurance.” Some members of the public who have read the advance copy of the book told me they think Uwe’s reform proposal is utterly fair and reasonable. It is time we act as a nation of grownups.