A star-studded Nigerian movie about corruption — and a subsequent text-messaging campaign to combat government graft — led a record number of citizens in Nigeria to report acts of corruption, according to a study in the journal Science Advances.

A star-studded Nigerian movie about corruption — and a subsequent text-messaging campaign to combat government graft — led a record number of citizens in Nigeria to report acts of corruption, according to a study in the journal Science Advances.

The two-part campaign generated 241 corruption reports from 106 communities in just seven months, according to the researchers, who are based at Princeton University; the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA); and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). A previous corruption-reporting campaign yielded less than 140 reports in a full year.

Commissioned by the study’s authors, the film suggests that people will take positive action to report crime if prompted by role models and given accessible avenues to do so.

“The policy messaging of our study is clear: Campaigns should make it easy for people to do the things they are already motivated to do,” said Betsy Levy Paluck, professor of psychology and public affairs at Princeton’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs. “In this case, the texting campaign made it free and simple for people to reply to a message that came to their phone, regarding an issue they found to be important. The film provided role models of other Nigerian citizens reporting corruption by text.”

Levy Paluck, who is deputy director of Princeton’s Kahneman-Treisman Center for Behavioral Science & Public Policy, conducted the study with Graeme Blair from UCLA and Rebecca Littman from MIT. Through their two-part field experiment, they sought to understand how to persuade a group of people to try a new form of community-minded action.

One way to change norm perceptions is to highlight the behavior of role models, whether they are real or fictitious. The researchers wanted to explore how this could be done through film.

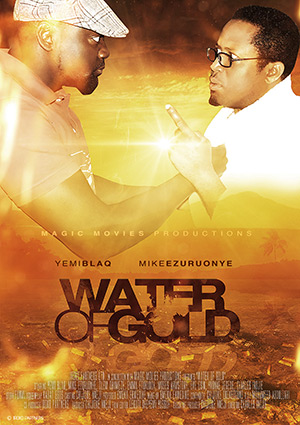

They commissioned a movie from IROKOTV in Nigeria, the third largest producer of Nollywood films in Nigeria. The two-hour film, “Water of Gold,” was written by Kabat Esosa and produced by Iroko Partners with Magic Movies Productions. It starred two big Nigerian stars: Yemi Blaq and Mike Ezuruonye.

The movie took place in four states in southeastern Nigeria, home to roughly 14.2 million people. Despite the region’s rich supply of crude oil, corruption at the level of international corporations, Nigeria’s federal government, and state and local officials have contributed to poverty and under-development or have not translated into local development. Today, local residents name corruption as the top problem faced by their country.

The movie took place in four states in southeastern Nigeria, home to roughly 14.2 million people. Despite the region’s rich supply of crude oil, corruption at the level of international corporations, Nigeria’s federal government, and state and local officials have contributed to poverty and under-development or have not translated into local development. Today, local residents name corruption as the top problem faced by their country.

The film follows the story of a poor fisherman named Natufe and his rags-to-riches brother Priye. The two are close until Priye leaves their village, eventually returning years later as a wealthy businessman. Against Natufe’s wishes, Priye begins to work with corrupt local politicians. Eventually, Natufe becomes outspoken against the corrupt system in which they live.

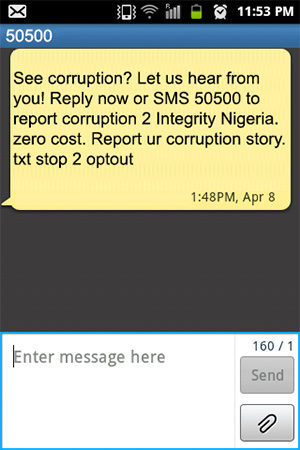

The researchers rolled out two different versions of the film. In both, a number was displayed on the screen four times, urging viewers to call a hotline to report corruption. It said: “See corruption? Let us hear from you! SMS 50500 to report corruption to Integrity Nigeria. Tell us your story. Text for FREE. Your number kept secret.”

What differed was the plotline of the film. In the “treatment version,” Natufe and a local activist set up a toll-free “short code” telephone number, used for mass text messaging, to encourage community members to report corruption. This took place in six scenes. In the “placebo version,” this part of the storyline is removed. In some regions, viewers were able to watch the treatment version of the film, whereas in other regions, viewers were exposed to the placebo version.

The second part of the study involved a mass text sent on a random day to all the people who watched the film. This allowed the researchers to study the effect of the messaging before and after the text nudge.

The second part of the study involved a mass text sent on a random day to all the people who watched the film. This allowed the researchers to study the effect of the messaging before and after the text nudge.

All told, the researchers received 3,316 messages from 1,685 different people. Among these, 241 individuals sent concrete corruption reports explicitly mentioning a specific act, person, or institution who had committed malfeasance. People most commonly reported bribes and embezzlement perpetrated by politicians, law enforcement, and those in the education sector.

“We were very excited to see this many people send in messages. When we first described the campaign to experts and activists on the ground in Nigeria, they didn’t think anyone would participate,” Littman said.

Seeing the role models of corruption reporters in the film encouraged viewers to report corruption, and separately, individuals who received the text message encouragement were significantly more likely to report corruption. The researchers think the film campaign may have caused reporting due to a perceived shift in norms regarding the community’s anger toward corruption.

“Our study shows that campaigns can use emotional narratives to mobilize collective action,” Paluck said.

Funding for the study came from an anonymous private donor and the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research. The research was approved by the Princeton Institutional Review Board, protocol #5813.

The paper, “Motivating the adoption of new community-minded behaviors: An empirical test in Nigeria,” first appeared March 13 online in Science Advances.