Despite the relatively large number of employees working in downtown Detroit, the city continues to be afflicted by urban blight, surrounded by a swath of vacant neighborhoods. Changing this pervasive phenomenon has been at the forefront for developers, city officials and groups like Detroit Future City, an initiative with a strategic vision for the city’s future.

Debuting a new economic model, a team of researchers from Princeton University and the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond have identified 22 neighborhoods that, if developed, could bring in millions of dollars in residential and business rents while attracting thousands of new residents to the city.

These neighborhoods — which include areas like Rosa Parks, Lower Woodward, Middle East Central, among others — differ significantly from those targeted by Detroit Future City, which mostly focuses on neighborhoods close to downtown.

The results are published as a working paper in the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

“Reviving Detroit requires coordination and buy-in from multiple developers, residents, and city governments. You can’t think small scale on this,” said co-author Esteban Rossi-Hansberg, Theodore A. Wells '29 Professor of Economics at Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs. “Our analysis shows there are mutual gains to be had by all parties. The gains would also be distributed across the city and beyond its boundaries, so coordination between counties is crucial.”

In addition to Rossi-Hansberg, the model was designed and evaluated by Raymond Owens and Pierre-Daniel Sarte, both of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. The economists focused on Detroit given its significant evolution from a world famous city to a “hollow shell” over the past 100 years.

The researchers constructed their model around what they call “development guarantees” — buy-in from the government or private institutions that guarantee a certain level of development in a particular area. The model accounts for businesses moving into the area, the location itself, and workers’ willingness to commute to that area.

The ideal development guarantee, the researchers argued, is one that ensures that developers are willing to build in areas in which people would be willing to live. The policy would help to trigger the entry of private developers and, if successful, would imply no actual resources from the guarantor. On the flip side, if the guarantee isn’t large enough, it could lead to undesirable outcomes — like the city having to buy properties that developers aren’t able to sell.

A similar but alternative proposal was advanced by Detroit Future City, whose strategic framework lays out a desired image of what the city should look like in 10, 20, and 50 years into the future. Detroit Future City’s most ambitious proposal involves 22 tracts, but the proposal was never quantified — until now.

The researchers quantify the gains and losses of alternative plans by Detroit Future City and others by modeling the employment decisions of firms, location and commuting decisions of workers, as well as the decision of developers to enter particular neighborhoods.

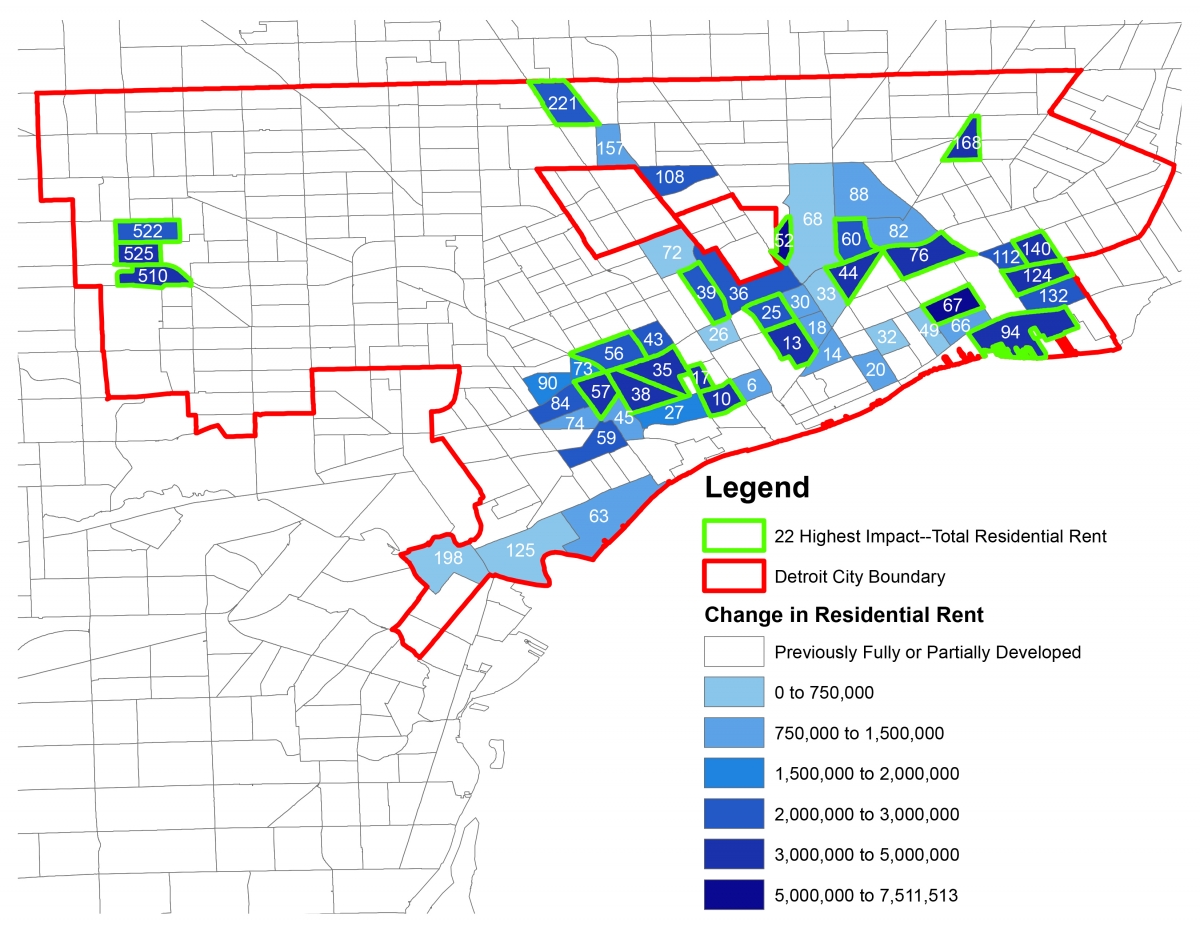

The Princeton-Federal Reserve researchers tested their new model on the city of Detroit and all surrounding counties and identified 52 census tracts (neighborhoods) across the city that are currently mostly vacant and generally in bad shape. Between the researchers’ model and Detroit Future City’s plan, only 11 out of 22 neighborhoods are shared.

One of the biggest differences is that the Detroit Future City proposal focuses on developing the areas closest to the downtown core, while the researchers’ estimates—which they call the “Best 22 Residential Plan,” covers some of the same areas but also areas in a wider outer ring. Although both policies promise gains, the difference can amount to several tens of millions of dollars and many less new residents.

The results in the study are based on a particular model of the city of Detroit and, as for any policy evaluation, depend on a number of assumptions that are described in detail in the NBER working paper, the researchers noted.

The study, “Rethinking Detroit,” was published in NBER as a working paper and was not peer-reviewed or subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications.