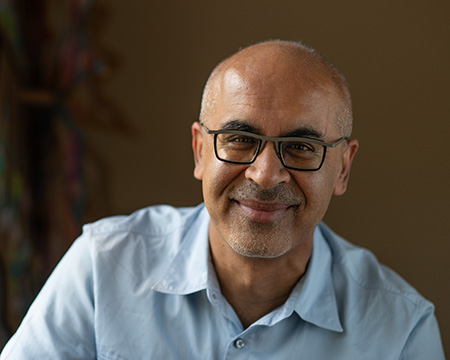

On a recent Tuesday evening, Varun Gauri stepped behind a lectern at the Princeton Public Library not to deliver a talk about political or behavioral economics—topics he teaches at the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs—but about Meena and Avi, the two characters in his debut novel who embrace Indian tradition by having an arranged marriage in small-town Ohio.

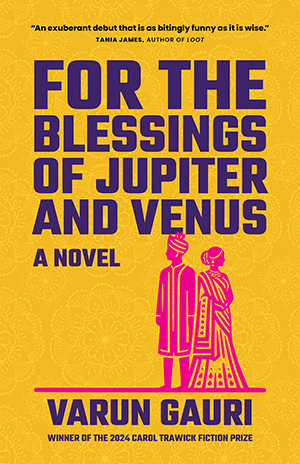

For the Blessings of Jupiter and Venus is an exciting new addition to the growing tide of literature by first- and second-generation Americans exploring what it means to hold multiple identities. Yet unlike his peers in the genre, Gauri is a former World Bank economist who teaches public policy as a lecturer at Princeton SPIA.

Gauri shared how a behavioral economist came to write fiction in the following interview, which has been edited and condensed:

Congratulations on your first novel! It's not every day you see an accomplished behavioral economist writing fiction. When did fiction become a part of your life?

Varun Gauri: I’ve always gravitated towards creative writing. For many years while I was at the World Bank, I didn’t really have the time to focus on it given family and work. But I kept the passion alive over the years. Even in my academic work, I lean towards narrative explanations. Stories help explain how people and social life may be more complicated under the surface.

You have an undergraduate degree in philosophy and literature, which makes me think you always had a love for the humanities. How do you see this background informing your work as an economist and a teacher of public policy?

VG: Philosophy has played a huge role in my professional career and academic writing. When I was at the World Bank, the 2004 World Development Report on service delivery tried to explain health and education outcomes through markets and electoral accountability, and I argued in it that morality, human rights, and legal institutions are another crucial accountability framework. Eventually I got interested in the philosophy of global fairness, and now I teach a course on development ethics at SPIA.

Has it been easy for you to explain your interest in fiction to colleagues in the empirical sciences?

VG: Everyone is supportive. Some researchers are like, “That's kind of interesting,” as if it’s a cute little hobby, but others can see the connections. I had a senior United Nations colleague who reported that on his vacation he had “wasted time reading novels.” He liked reading fiction, but he was betraying a social norm that stories aren’t considered serious but an indulgence.

Novels make me feel alive. It's a sense of connectedness to the world. They give me energy. They build my intuitions for what makes people tick, which is what social science is about. There's also social psychology research that shows when people read literary fiction, they are less parochial, more willing to support others, and better understand other people’s minds. When you read, you grow alert to being, rather than your model of it. That's really valuable.

As a fellow South Asian immigrant who has been subjected to parental pressure to choose a reliable career, I have to ask whether you always wanted to be a novelist but did the economist thing to appease your parents.

VG: If I really wanted to appease my parents, I would have been a doctor. [Laughs] I didn’t choose medicine or engineering, but my parents had heard of the World Bank, so that was good. If I’d followed my passions after college, I might have studied the history of religions or something like that, but the humanities were considered a little weird in my family. I definitely have a political passion and wanted to make the world a better place, which is why I got into development economics. I chose development because I was always interested in global fairness and wanted to do something for India, which I used to think of as my home country.

In For the Blessings of Jupiter and Venus, you explore such relatable themes for any of us third-culture kids. On its surface, the story is about a newly married couple trying to find happiness in their marriage, which hasn't matched either of their expectations. Yet the characters and their choices are so interesting. Meena is a globetrotter who opts for an arranged marriage, and Avi is a fairly traditional guy who falls for this bold, unconventional woman. What are you trying to explore through them?

VG: It's not necessarily about arranged marriage, or not only that, but about the uses and limits of life plans and models. Meena and Avi have this idea of how marriage is supposed to be, how families are supposed to be, what will make them happy. They realize over the course of the novel that things are more complicated and messier than they imagined, and they need to evolve, let go of their old ideas and frozen identities. They realize they’ve been pursuing a postcard of a family instead of an actual family and marriage.

It reminds me of being a student in some ways: I had this idea of what it might be like to be an economist. In Avi's case, he thinks he's going to be a politician and make his parents and community happy. He has to let go of that model and focus on living for himself, on the basis of his actual intuitions and feelings.

You're on a book tour, but you were also just in Europe with your students investigating government bureaucracy. How are you finding the juggle or balance of these two worlds? Is there anything you gain from one that you apply to the other?

VG: I always enjoy the openness to the world of students at Princeton SPIA. They are really alert to what’s happening. That kind of energy relates to the protagonists in my book, who are also in their 20s and charting their way. I’m definitely enjoying remembering that time in my life.

Where do you expect your writing to go from here? Are there other novels you plan to write? Can you share anything about their themes?

VG: I have a short story set on a university campus that may turn into a novel. The themes I’m interested in are related to the first novel: authenticity, characters trying to figure out who they really are.

Authenticity is becoming increasingly more complicated in the world of AI: What is a real essay, a personal thought? What do I believe for myself as opposed to what an algorithm points me towards?

The short story is set in the near future, not when cyborgs are controlling us but when we may have more AI assistance in making decisions. This is going to result in some clarity and some confusion for a while. We’ll need to think through the personal and social consequences of some of the choices we’re making.