In October 2017, after declaring Catalonia’s independence from the Kingdom of Spain pursuant to an affirmative majority vote on a referendum for secession, Carles Puigdemont, the leader of the regional government of Catalonia — an autonomous community of the Kingdom of Spain — fled to the Kingdom of Belgium to avoid arrest on charges of sedition and rebellion. The Spanish government annulled the results of the referendum and ordered new elections for the region of Catalonia, which resulted again in a majority for the parties supporting independence. It appears uncertain how this phase in the long-standing Catalan strife for more self-governance will end, but it also seems that Madrid will neither compromise, nor negotiate.

The developments in and around Catalonia are being watched closely, worldwide, by the members of governments, diplomats, scholars, opinion-makers, those interested in Spain, those intrigued by self-determination (both conceptually and in practice), and also by those who aspire for greater autonomy, self-governance, or even sovereign independence.

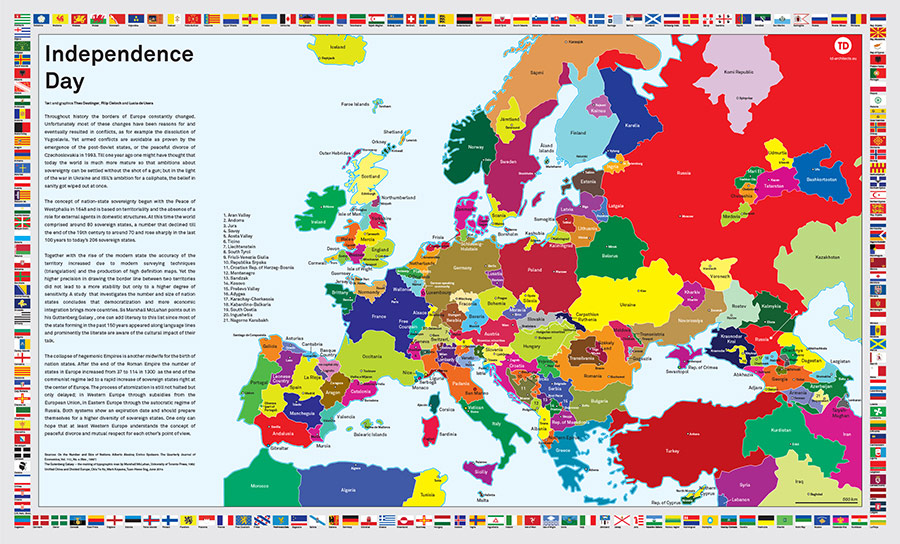

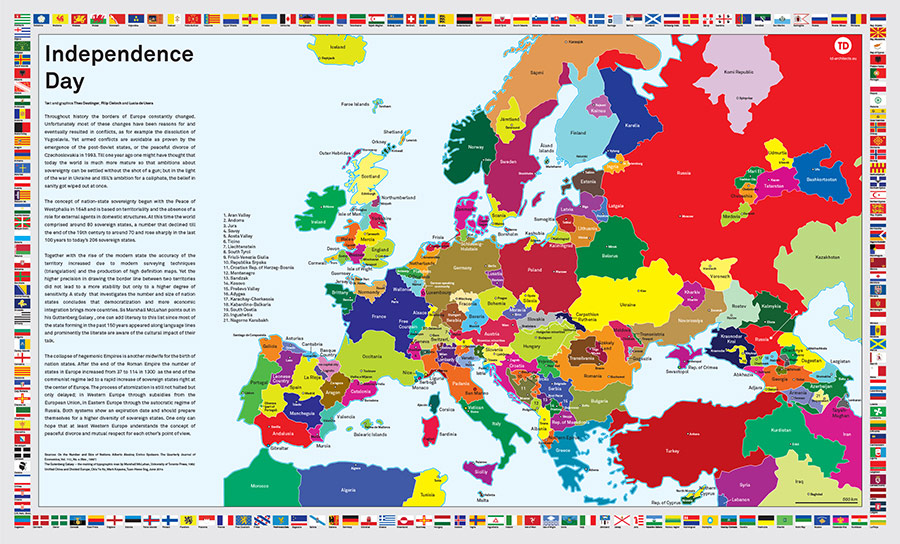

And Catalonia is not alone. Thematically related events have taken place elsewhere, such as: in March 2014, the referendum on the status of the Crimean peninsula, which resulted in its secession from Ukraine; and also in 2014, the Scottish Independence Referendum, which some members of the Catalan independence movement see as an ongoing sister movement in Europe. Furthermore, in September 2017, a referendum on self-determination was held amongst Iraqi Kurds, and in June 2016 the people of the United Kingdom voted to exit the European Union (EU), a process that came to be termed ‘Brexit.’ In her letter to the EU, British Prime Minister Theresa May stated, “The referendum was a vote to restore, as we see it, our national self-determination.”

These developments signal to many a renaissance in the relevance of self-determination in our times, according to Wolfgang Danspeckgruber, director of Princeton University’s Liechtenstein Institute on Self-Determination (LISD), based within the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs.

“Today we are confronted with a critical challenge: The global order as we have known it since 1945 doesn’t seem to work anymore; however, a new order isn’t established yet; thus, anything can be possible, and we have to be ready to ‘think the unthinkable’,” says Danspeckgruber.

A new generation, and rapidly developing science and technology, are primary factors driving the reinvigoration of self-determination interests, according to Danspeckgruber. Emerging leaders across the globe have increasing access to “hitherto unimaginable” technologies — from social media to robotics — and see opportunities for change in a shifting, interconnected world increasingly influenced by new state and non-state actors. In addition, during the long period of relative peace in many parts of the world, there is mounting discontent with the old order — like in Europe, with the EU, and in Russia following the disintegration of the Soviet Union — while the older generation, which experienced major crises and wars, is petering out of leadership.

“The appeal of self-determination seems to have ‘come back with a vengeance,’ including in places such as Western Europe, the Balkans, Eastern Europe, and the Caucasus, all regions which have experienced crises in the recent past. For too long have continued grievances and problems been ignored there. When coupled with disrupted communications, self-determination aspirations can sometimes also be instilled, and instrumentalized, by other powers,” Danspeckgruber suggests. “‘Determine your destiny’ has obtained a powerful attraction again. While the principle of self-determination is firmly anchored in international law — from the Charter of the United Nations to the International Bill of Human Rights — it is perceived to be in conflict with the principle of sovereign territorial integrity in particular. While enhanced self-determination should not necessarily mean secession, here can be tensions between self-determination and other principles, which need to be recognized and addressed.”

"If a community has the right mix of educated human capital, a favorable geopolitical location, and economic prowess, it might feel even more empowered to strive for wider self-governance and perhaps independence — this seems also to entice and activate the emerging generation of communal leaders — particularly if they perceive that their demands to central authorities are being ignored,” added Danspeckgruber.

These complexities might rightly give an analyst pause, as self-determination can both be a blessing or a curse, a dream or a nightmare with a fearful portent of potential bloodshed and destruction when it takes a state shattering form — in the words of Mao Tse-tung, self-determination can sometimes be “the spark that…start(s) a prairie fire.” However, no two self-determination cases are alike — as much as each community is unique, its historical and geographical experience are unique too. And according to Danspeckgruber, the ultimate objective of any self-determination initiative should be to provide the foundations for a better future, including peace, prosperity, and justice for the community.

To prevent or alleviate the dangerous deterioration of a self-determination crisis, experts and mediators can assist to educate, and raise awareness of its possible, unintended consequences for the parties involved. Mediators might also try to facilitate private communication, listen to grievances, carry messages, and suggest compromises between the parties to de-escalate tensions. Oftentimes, Danspeckgruber notes, the parties involved have only limited contact with one another; in addition, community leaders may have unrealistic objectives and/or misguided information. It can therefore be helpful to offer impartial, precise, and accurate information about relevant international norms and institutions, and potential consequences and costs. But all this can only be fruitful if the parties involved are interested in such information and mediation, he adds.

For example, for a new entity wishing to be recognized as a sovereign member of the United Nations and to enjoy the full benefits of such standing, it must be accepted by the General Assembly of the United Nations, upon agreement by the U.N. Security Council and its permanent members — China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States. The European Council, which is made up of the heads of state or government of the (still) 28 European Union member states, like Belgium, Croatia, France, Germany, Slovenia, Spain, and still the United Kingdom, makes decisions regarding who is to be accepted into the EU as a new member.

“If a given community of an existing EU member state were to secede, it would be unadvisable to expect the members of the European Council to approve an application for EU membership easily or quickly, as other states might be unwilling, or tentative, to establish such a precedent," posits Danspeckgruber.

Efforts to privately assist in a self-determination crisis, and to eventually bring the various parties together to enable earnest, meaningful discussions, can only be fruitful if the relevant actors are really interested in participating, says Danspeckgruber, who has been involved in related private diplomacy since the Balkan crisis in the 1990s. For such an actor, he adds, it is critical to be seriously informed, neutral, perceptive, very discrete, and to interact with all parties in person.

“One has to travel to the region, to breathe the air there, and to meet the people. One has to try to grasp the culture and the history, of the community and, ideally, also of the wider region,” he recommends. “While this is part of validation and mutual respect, this also touches on identity and the pride of all actors involved, critically to earn their trust. In addition, all of my local visits became also an important personal education, and permitted [me] to interact with the people and their leaders in their environment. The more one obtains the trust and confidence of the parties, the higher the chance for meaningful, earnest interaction, and eventually positive talks, although this process might take some time.”

Importantly, the longer a self-determination crisis remains unresolved, the more it is likely to become costly and difficult to resolve. In addition, frequently there are external actors or other spoilers who might wish to stoke, and in doing so capitalize on the self-determination strives of a community for their own interest, says Danspeckgruber.

In Danspeckgruber’s view, this last point is key: The appeal of self-determination is surging in part because of its potential as a tool. The scope of an external force’s potential interference in a community’s internal dynamics is increasing, particularly due to the power of real-time social media, advanced information technologies, and facilitated travel.

“One can observe the attempts of outside powers to meddle in many modern self-determination cases via disinformation and manipulation to influence votes or referenda,” warns Danspeckgruber. “While such tactics are age old, today’s advanced technologies offer new highly sophisticated techniques, which are oftentimes hard to detect and hence difficult to combat. On the other hand, a severe self-determination crisis can potentially weaken the state in question, and can destabilize its entire region. A European Union with many crises and an eventual Brexit, (and thus without the United Kingdom), might certainly experience some turbulence and not necessarily be stronger — at least not in the short run. Some actors in our world and time might welcome just that.”

Furthermore, self-determination interests require resources. A community aspiring to greater independence needs to be able to assure its economic survival. The more this seems to be feasible, the greater the appeal for more self-government, posits Danspeckgruber. China, for example, offers new investment and possible market access to many communities in many places in Europe. This can enhance the appeal for more independence in those societies — particularly if there are grievances with the central authority, Danspeckgruber finds. The rising number of powerful non-state actors, which often act independently and sometimes have considerable economic, financial, or even quasi-military resources, can also contribute to emerging self-determination issues.

With all of these factors in our seemingly unruly world taken into consideration, it is important to develop methods and tools to prevent self-determination initiatives from escalating into severe crises, or from spilling over into violent, destructive conflicts with wider regional destabilization potential, according to Danspeckgruber, who sees non-polemic research and education, information, and neutral mediation to be the appropriate, anticipatory response. In view of the increase in self-determination suits around the globe, LISD works to develop and implement innovative initiatives to tackle both the opportunities and challenges they present.

LISD will host a Roundtable on Self-Determination on Thursday, Feb. 22 from noon to 4:30 p.m. in 019 Bendheim Hall. Princeton University students and faculty are encouraged to attend.

As the founding director of LISD, Wolfgang Danspeckgruber is interested in research, teaching, and innovative scholarship on self-determination, and contributions to local and national peace and stability while also educating the next generation of leaders. The LISD was founded in 2000 through the generosity of Prince Hans Adam II., the Reigning Prince of Liechtenstein.

“The appeal of self-determination seems to have ‘come back with a vengeance,’ including in places such as Western Europe, the Balkans, Eastern Europe, and the Caucasus, all regions which have experienced crises in the recent past. For too long have continued grievances and problems been ignored there. When coupled with disrupted communications, self-determination aspirations can sometimes also be instilled, and instrumentalized, by other powers,” Danspeckgruber suggests. “‘Determine your destiny’ has obtained a powerful attraction again. While the principle of self-determination is firmly anchored in international law — from the Charter of the United Nations to the International Bill of Human Rights — it is perceived to be in conflict with the principle of sovereign territorial integrity in particular. While enhanced self-determination should not necessarily mean secession, here can be tensions between self-determination and other principles, which need to be recognized and addressed.”

“The appeal of self-determination seems to have ‘come back with a vengeance,’ including in places such as Western Europe, the Balkans, Eastern Europe, and the Caucasus, all regions which have experienced crises in the recent past. For too long have continued grievances and problems been ignored there. When coupled with disrupted communications, self-determination aspirations can sometimes also be instilled, and instrumentalized, by other powers,” Danspeckgruber suggests. “‘Determine your destiny’ has obtained a powerful attraction again. While the principle of self-determination is firmly anchored in international law — from the Charter of the United Nations to the International Bill of Human Rights — it is perceived to be in conflict with the principle of sovereign territorial integrity in particular. While enhanced self-determination should not necessarily mean secession, here can be tensions between self-determination and other principles, which need to be recognized and addressed.”